Pictured: Jacek Kalisztan (Mateusz Kościukiewicz) before losing face in 'Mug', a Polish allegory co-written and directed by Malgorzata Szumowska. Still courtesy of Bulldog Film Distribution UK

‘Losing face’ is an English expression for losing respect. In the Polish film, Mug (Twarz), Metallica-loving construction worker, Jacek Kalisztan (Mateusz Kościukiewicz) loses half his face, requiring a transplant, and almost all the respect from his family and girlfriend. He ends up boarding the very bus on which he used to see his beloved Dagmara (Malgorzata Gorol) leave the village, having no way to meaningfully contribute to anyone’s lives. He is worth just twenty zloty, the small amount collected for him at Sunday service. As we see a wide Kaftan-like basket being passed around, no one is moved to offer money to pay for the expensive immune-suppressants that the Polish health service won’t fund.

Co-written and directed by Malgorzata Szumowska, who is married to her lead actor – Kościukiewicz previously had the lead role in her 2013 film, In the Name of (W imie...) – Mug is pitched somewhere between black comedy, broad satire and allegory. It never quite comes together, since it abandons its protagonist in much the same way as the community it depicts. It is notable for its stylistic flourishes. In many scenes only the left side of the frame is in focus, a reflection of the loss of vision in Jacek’s and, by extension, society’s right eye. There are also dream sequences, mostly involving Dagmara – again from Jacek’s point of view – lapses into slow motion and striking uses of static camerawork. There is fantasy too. At one point, an old woman swats away flies on the body of her deceased husband as his coffin lies open. After the fourth swat, the dead man tells her off.

The opening is something else again. We see a large number of people gathered silently, dressed in winter clothes, waiting. We notice on the far left of the frame one of the crowd members in profile. We see the cause: a 70% off ‘underwear’ sale that requires customers to strip to their under-garments before racing through the store to secure a reduced-price wide-screen television. Struggles ensure. One TV is wrested from a customer’s hand. An overhead shot shows the melange. The sequence ends with a woman in her underwear staring at the vacant space where once TV screens were piled up, scarcely able to accept that she will have to return home empty-handed.

Pictured: The happy couple (Malgorzata Gorol and Mateusz Kościukiewicz) in 'Mug', co-written and directed by Malgorzata Szumowska. Still courtesy of Bulldog Film Distribution UK

Jacek, with a friend – or is he a family member – is one of the lucky ones. He irritates his companion by driving too fast (‘careful, you might damage the TV’) whilst playing Metallica’s ‘Hardwired’ on the car stereo. Szumowska’s static camera records the car wending its way at speed up a mountain road, the song ending at the words ‘hardwired to self-destruct’. Szumowska uses the refrain later, ending at the same point; not very subtle, but not meant to be.

At the family farm, Jacek’s brother-in-law (Robert Talarczyk) is collecting money for the Christmas pig. He is 400 zloty short. Jacek doesn’t contribute. He doesn’t say why, but the inference is that he is saving to travel to London. Jacek’s older sister (Agnieszka Podsiadlik), who we see wandering in and out of view, wishes she could go too. The frame is composed so that the brother-in-law remains in the centre, rooted to the spot and, by extension, rooted to his principles. He will later curse his wife for not satisfying him sexually, devoting her energy to looking after ‘Twarz’ (Mug) instead.

The Christmas pig is purchased nevertheless. We watch from a discreet distance as the animal is led away, noticing almost casually that one of the men is holding an axe, before the pig squeals as it is slaughtered off-camera.

We see Jacek place a large white cross above the grave of a family member – his grandfather, perhaps. ‘Where’s Christ?’ he is asked. The family dog runs on top of the grave in an excitable fashion. We imagine it might knock the cross over, or defecate on the grave.

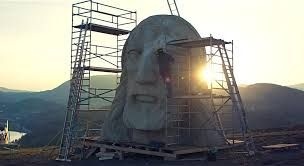

Pictured: Christ the Redeemer under construction in 'Mug', a drama in Polish co-written and directed by Malgorzata Szumowska. Still courtesy of Bulldog Film Distribution UK

Dagmara works at a corner shop. A man struggles to ask for something – the scene prefigures Jacek’s difficulty being understood. The customers like Jacek. Jacek loves Dagmara. He proposes to her on a swaying footbridge. Filmed from behind, Jacek’s hair, blown by the wind, slightly obscuring our view, we see the joy of Dagmara’s response, jumping into his arms. They have their picture taken at a local photographer’s, giggling throughout as the photograph greets every pose with excessive enthusiasm. Later, Jacek will look at the photograph, still in the shop, unclaimed.

In long shot, filmed again from a discreet distance, we see Dagmara board a bus. Jacek stands behind it and pretends to push it as the bus moves away. Szumowska and her cinematographer, Michal Englert, also the film’s co-writer, know how to stage a perspective shot. They will also disarm the viewer with a Christmas disco sequence, in which one woman dances before us to electronic music, the DJ nodding, before several partygoers take to the dance floor, including Jacek and Dagmara. Later at a wedding, Jacek will imagine an orchestra playing the same piece of music as he recovers his long hair and good looks and lures Dagmara away from her new boyfriend.

A pivotal scene involves a young boy holding up a pig’s head and shouting, ‘death, death’. The tone is joyous. Indeed, Jacek’s dog is keen to tuck in to the otherwise wasted head. It chases the head around. Something dark is about to happen.

Jacek works on a building site where a large statue of Christ the Redeemer is being constructed; it is paid for with parishioners’ funds. The intention is to unveil a monument to rival Rio de Janeiro and stimulate tourism. This is not to say that the community likes outsiders. At a gathering, a racist joke is told – three men of various nationalities dive from a building. Who wins? Society! In another racist joke, a child from another ethnic group explains that he wants a shit. ‘Hang on – I’ll cut you off a slice.’ Poland is notorious for its racism, which is reflected here without reply. In the film, racial intolerance is replaced by facial intolerance.

The accident is something of a coup-de-cinema. Filmed in slow motion, Jacek falls backwards into the black abyss. Strangely, he is able to walk and looks down at his feet as he is evacuated from the scene, the camera assuming his point of view.

The injury – Jacek’s facial disfigurement – doesn’t logically stem from the accident. For one thing, he falls backwards, not face first. We wonder why his spine isn’t damaged. Szumowska doesn’t insist on realism, preferring instead to make the injury metaphorical.

Jacek has his face rebuilt, but his right eye won’t open fully and he is unable to speak coherently. He moans, as if heavily sedated. Watching a dancer on television, he imagines Dagmara prancing naked with a taper. Whilst he sleeps, she visits him, wearing a white medical coat. Her pace slows as she gets a better view of his injuries, then she steps to one side.

Pictured: One facially-disfigured man and his dog in 'Mug', a Polish film co-written and directed by Malgorzata Szumowska. Still courtesy of Bulldog Film Distribution UK

One of the film’s most striking compositions has a member of the hospital’s medical staff holding a phone so Jacek can hear as we see his family members, separated from him by two panes of glass, speaking to him: ‘don’t worry, you’ll be all right.’ He is broadly okay and becomes an object of interest, surrounded by locals wanting a selfie with him.

Nevertheless, Jacek is denied disability benefit and is told he can work. But as what? One of the panel members suggests ‘a messenger’. Jacek sends him a message, baring his buttocks. The decision is not open to review.

In another striking sequence the family gathers to watch Jacek’s sister give a television interview. Her answers fall short. She neither asks for something nor conveys optimism. ‘You could have smiled more,’ complains her husband.

Jacek searches for Dagmara. She is not in the shop. As he leaves, he sees a picture of himself on the front of a magazine and chuckles. ‘Would you like an autograph?’ he asks in his muffled way.

The initial collection at church is generous, but the response ebbs away. Dagmara’s mother closes the door on Jacek. He finds work as a model, though on the two assignments, he is told not to smile. Later only Krystyna, a woman on television wanting to win a vote to celebrate her virtue, says she’ll take Jacek – at the end, Jacek may be making his way to her home.

Dagmara does indeed reject him and dances in a bar whilst removing her clothes. Jacek tries to cover her up and a fight ensues.

Jacek’s family make separate visits to confession. Jacek’s mother doesn’t recognise him and complains that he has been possessed. An exorcism is proposed, but there is a year-long wait. Later, Jacek is ‘exorcised’, the family priest recording it on his cell phone. However, Jacek doesn’t take the exorcism seriously, hamming it up before asking the priest, ‘are you mad?’

A family member dies and there is bickering over land rights. Jacek is withdrawn. He is called ‘mug’ and a Satanist. He initially enjoys scaring the local kids. As a novelty, he has outstayed his welcome.

What of the statue? It is pointing in the wrong direction. The final image is of the spectacular statue of Christ the Redeemer, palms outstretched, with his head turned ninety degrees to the right. An inter-title tells us it is based on a real monument.

With no likable characters, save for Jacek’s sister and the ineffectual family priest, and no redemption, Mug offers a grim reflection of life and attitudes in rural Poland. The comedy doesn’t really translate to a non-Polish audience. Rather our response is to be appalled - appalled but also indifferent. We don’t feel anything for these self-interested people. What should we feel for Poland? Mug is an example of anti-nationalist cinema that seeks to provoke by offering an appalling reflection of society. However, such a response depends on a Polish audience’s willingness to engage. Judging by the audience response I experienced at a Polish language screening in West London, Poles would prefer simply to close the curtain on reflections not to their taste.

Reviewed at Cineworld Feltham, West London, Screen Three, Saturday 8 December 2018, 20:50 screening