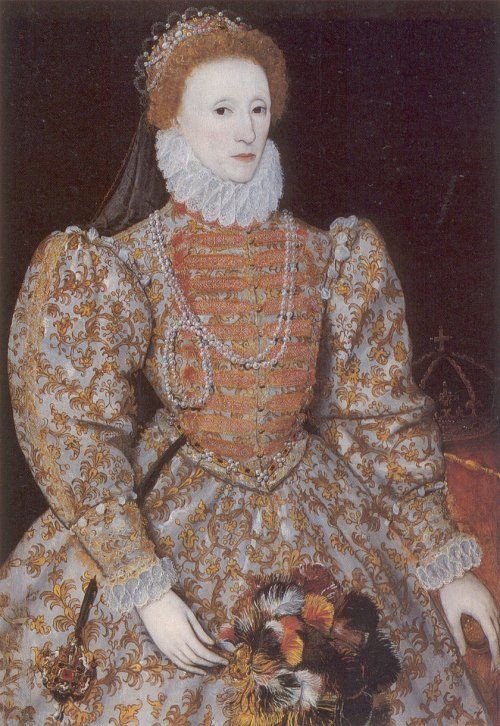

When Elizabeth I ascended the throne in 1558, she was the most eligible woman in Europe and, before long, had some of the most powerful men in the world clamouring for her hand in marriage. With her father’s auburn hair and her mother’s dark eyes and olive complexion, Elizabeth was widely reputed to have been physically attractive, described by the Venetian ambassador Giovanni Michiel in 1557 as “tall and well formed, with a good skin, although sallow. She has fine eyes and above all a beautiful hand of which she makes a display…” Since beauty was believed to amplify female power, it was imperative that Elizabeth outshone everyone around her, in order to support her right to the throne. And outshine them she did. Every last part of the Queen’s carefully crafted public image was honed to perfection. She designed everything to convey her right to rule in a world where women were not expected, or encouraged, to exert independent authority, and where youth, health and fertility were attributes to be celebrated above all others. But while it was easy to portray Elizabeth as such in her youth, when her physical appearance bore witness, what was to be done as she grew older? In her later years, the Queen was obviously aging, with rotten teeth and thinning hair. She was clearly beyond childbearing image, and yet still without a successor. The situation had the makings of an Elizabethan public relations nightmare.

PICTURE PERFECT:

That Elizabeth was an unmarried female monarch could not be ignored. In fact, it had to be transcended to ensure the continued loyalty and faith of her subjects. And like monarchs before her, Elizabeth used portraiture to manipulate her public image. She employed symbols and emblems from biblical, classical and mythological sources to convey an image of an all powerful ruler. To deliberately encourage Elizabeth’s image as the ‘Virgin Queen’, she adopted common symbols of virginity as personal emblems. Pearls – associated with purity – were often encrusted on Elizabeth’s gowns, or hung around her neck. As the Queen walked through the ha her royal palaces, tiny seed pearls are said to have fallen from her skirts as she moved. The white rose of purity associated with the Virgin Mary was another popular addition to her clothing, as was the phoenix, a mythical, self-perpetuating bird and a symbol of chastity. And Elizabeth often wore crescent moon jewels in her hair, symbolic of the Roman virgin goddess, Diana. Elizabeth’s wardrobe itself was designed to impress and she never appeared in public without full make-up and sumptuous clothing.

While in private she preferred to wear simple gowns, Elizabeth knew the value of clothing as symbol of status and power, and dressed to to reflect her position. “We princes, I tell you, are set on stages in the sight and view of all the world duly observed; the eyes of many behold our actions, a spot is soon spied in our garments; a blemish noted quickly in our doings”, she declared in a speech to Parliament in the 1580s. Not that there was much chance of Elizabeth ever having to wear a marked gown: at her death in 1603, some 2,000 gowns were recorded in her wardrobe and, from an inventory compiled in 1587 by Blanche Parry, Lady of the Bedchamber, we know that Elizabeth had 628 pieces of jewellery at that time.

IMAGE CONTROL:

The Queen’s public image was of paramount importance. In an age without television or social media, one of the fastest ways of sharing a carefully selected image of a monarch was via money In 1560-61, Elizabeth set about restoring the currency of England, which had been dramatically debased during the reign of Henry VIII. The old coinage, so reduced in value that it damaged trade relations and did little for the reputation of the monarchy, was withdrawn, melted, and replaced with newly minted coins of precious metal, each featuring an image of Elizabeth herself. Now every subject could own a tiny portrait of their Queen. Such images of the monarch were carefully choreographed and changed little throughout her reign. In 1563, in a move to regulate the production of her portrait, Elizabeth declared that a ‘pattern’ would be created that should then be copied by other painters. The painting of Elizabeth known as the ‘Darnley Portrait’ was one such pattern. Created in around 1575-6, it was used and re-used by artists. into the 1590s, helping to create the mask of youth and beauty that surrounded Elizabeth until her death. As the Queen’s closest advisor Robert Cecil commented carefully: “Her Majesty commands all manner of persons to stop doing portraits of her until a clever painter has finished one which all other painters can copy. Her Majesty, in the meantime, forbids the showing of any portraits which are ugly until they are improved.”

TO BE CONTINUED...

ELIZABETH (The Real Face) (P1)

Posted on at