MAN OF ACTION:

The defeat of Persia in 479 BC by no means ensured that Athens was to enjoy decades of unbroken peace. Anything but, in fact. Fifth- century Greece was a complex web of states, all bound up by various treaties and with competing interests. So the prospect of conflict was never far away.

The growth of the Athenian Empire, meanwhile, was a cause for concern to its former ally just 150-or-so miles to the southwest: the formidable Spartans. Few were surprised, then, when an uneasy peace finally cracked in 431 BC, and the two leading city-states in Ancient Greece became embroiled in what would become known as the Peloponnesian War, lasting until 404 BC.

Far from sitting in a philosophical ivory tower, Socrates saw his fair share of action. Serving as a foot soldier, he won admiration for putting his own safety at risk while protecting others when the Athenian forces were on the retreat from defeat at Delium in 424 BC. Not that anyone should have been surprised – at Potidaea in 432 BC, during one of a number of conflicts that led to the Peloponnesian War itself, he had saved the life of a brilliant young soldier named Alcibiades by refusing to desert him on the battlefield. Alcibiades later won a medal for bravery, but admitted that it was Socrates who really deserved it.

For all the friends and admirers that Socrates won, he also built up his share of those who mistrusted and resented him. When, in 423 BC, Aristophanes lampooned Socrates at length in his play The Clouds, the audience would have been amused by his daft portrayal. He portrayed Socrates as the Ancient Greek equivalent of a nutty professor, lounging around in a hammock, measuring how high fleas jump and worshipping the clouds and scientific phenomena rather than the gods. A few years later, when Socrates’ reputation had fallen, the perception of him as a blasphemous cloud- worshipper would turn dangerously toxic. His choice of friends didn’t help, either.

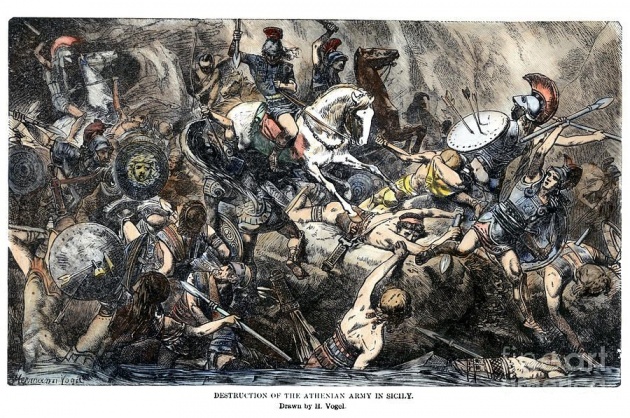

After having been saved in battle by Socrates, Alcibiades went on to become one of Athens’s greatest generals and inspiring statesmen. He was also one of its most opportunistic, maverick and morally elastic ones. When, in 415 BC, he fell out of favour while on a doomed expedition to Sicily, his reaction was to transfer his allegiances to Sparta and then advise them in campaigns against the Athenians. Socrates, tainted by association, must have winced, even more so when Alcibiades then cropped up in Persia, similarly offering his guidance in return for the promise of grand rewards.

Things really got tricky for Socrates, though, when the once-unthinkable happened to Athens in 404 BC: defeat by Sparta in the Peloponnesian War. The Spartans promptly swept away Athenian democracy and installed an oligarchy called The Thirty, who ruled with terrifying tyranny – about five per cent of Athens’s population is said to have been slaughtered during its brief rule. Socrates wasn’t afraid of tyrants any more than enemy soldiers and, true to his ideals, put his life in jeopardy by refusing orders from The Thirty that he thought were unjust. Ironically, though, it wasn’t The Thirty that did for him, but instead the regime’s overthrow and the return of democracy after just 13 months. Despite his refusal to play the oligarchy’s tune, Socrates was again tainted by association with it – a number of its members had been former friends of his.

CONDEMNED TO DIE:

A resentful Athenian populace was looking for blood, and here was an obvious target. That blasphemous ‘cloud worship’ came back to haunt him. Tried by a jury of 501 and condemned to death for impiety by a majority vote of 60, Socrates still had a chance to save himself. Typically, he didn’t take it. Athenian law allowed condemned men to suggest an alternative punishment such as exile. But for Socrates, taking this course would have effectively amounted to an admission of guilt and, as far as he was concerned, he had done nothing wrong. He suggested he pay a token fine and be looked after at the state’s expense for the rest of his days: this didn’t go down well.

Socrates’ friends offered to raise money for a much greater fine, but they had missed the point. He had no interest in living. For all his life, he had been in control – of his thoughts, of his actions, of his philosophical debates, of his destiny. Now he had turned 70 and old age was beginning to creep up, he could see a time where that control might start to wane and that, for him, was an unacceptable prospect. Above all, Athens’s greatest thinker also wanted to be in control of his own death. And if now was the time for that to happen, then so be it.

SOCRATES (The Man Who Asked Why) (Part 2)

Posted on at