Directing alone is not the pinnacle of a career in the film industry. For men, it is being a producer-director, having total control of the final film. You start off with a hit movie or two as a director (sometimes as a director-for-hire) and then move into production. With a slate of films in development and properties (scripts, stories) that you have acquired, you can go from one film to the next without necessarily being ‘hot’ (i.e. in demand). Being ‘just’ a film director depends on success. If you have made a hit film in a certain genre, you might get hired for a similar sort of movie. But then after a hot streak, you might find yourself waiting years to get a movie made. The film industry is a fickle business. The way to tackle it is in the Steven Spielberg-Steven Soderbergh route, with bursts of films pumped out, one after another. Both have on occasion released two films in a single year.

But there are few woman producer-directors. Barbra Streisand comes to mind but, for her, film directing has been an occasional occupation. Women generally work with supportive producers, like Jane Campion with Jan Chapman. Kathryn Bigelow (‘Zero Dark Thirty’, ‘The Hurt Locker’) has moved into production, but her main backer is Megan Ellison, the founder of Annapurna Pictures, who also works with David O. Russell, Paul Thomas Anderson and Mike Mills.

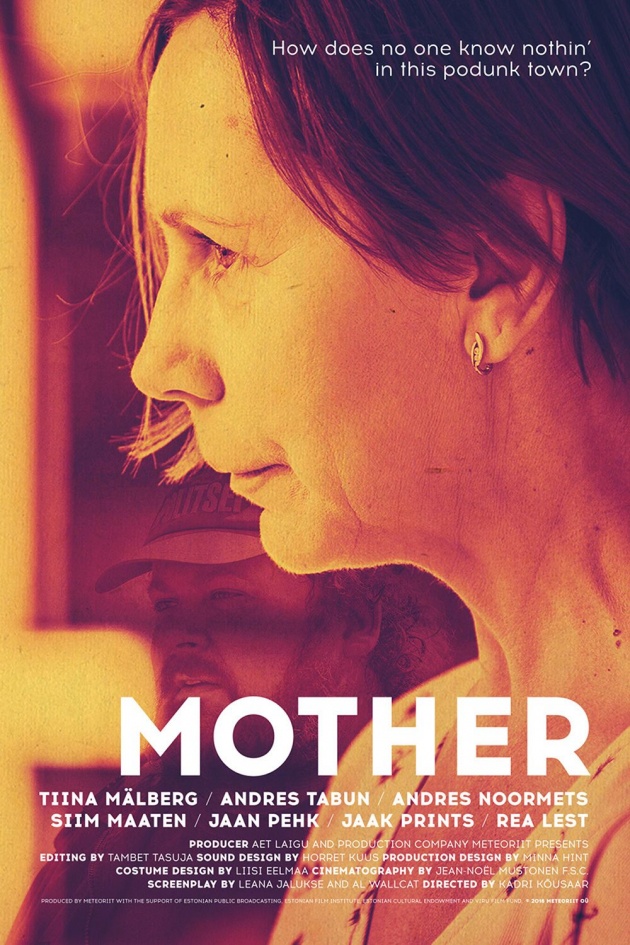

If you are not in film production and not regularly working as a director, what do you do? Diversify. The Estonian director, Kadri Kðussar is also an actress, screenwriter and novelist. If the phone doesn’t ring or an important email doesn’t arrive – write something. Kðussar worked as a director for hire on ‘Ema’ (Mother), a film she did not write – the script by Leana Jalukse and Al Wallcat won a competition. The production process was spectacularly smooth – pre-production in June 2015, shooting in August, in Estonian cinemas in January 2016. Wow! Contrast that with the recent film version of ‘Dad’s Army’, shot in 2014 but released by Universal Studios – as planned – in February 2016, and it flopped. Estonia sounds like a great place to make a movie, where filmmakers don’t have to wait for release windows.

‘Ema’ – there are many films called ‘Mother’, from directors such as Vsevolod Pudovkin, Bong Joon-ho and Albert Brooks, not to mention ‘The Mother’ written by Hanif Kureishi and directed by Roger Michell and ‘Mia Madre’ by Nanni Moretti – is a slow drip of a film, in which the plot is more important than the characters. In it, a popular school teacher, Lauri (Siim Marten) has been shot and left in a coma, cared for in the upstairs bedroom by his mother, Elsa (Tiina Mälberg). When we first meet her, Elsa is at a vegetable stall in the town square and is offered produce. She buys broccoli, in a state of shock, going through the motions. She has a meal with her hunter-gardener husband, Arvo (Andres Tabun) with whom she does not speak. His meal has meat and sauce; hers is just a single boiled potato, peeled not sliced, and broccoli. There is not even simmering rage or indifference between them. It is just that they are in parallel worlds in their marriage, as if arrived at as a form of truce. Elsa attends to Lauri at the end of the day, feeding him by tube, washing him. You can see why Lauri might have been popular – the actor playing him looks like Viggo Mortensen. Aragorn with bed sores – you can imagine the box-office appeal.

Lauri blinks both otherwise keeps his eyes open, as if preserved in a mausoleum – the last time I saw his like, it was Lenin in Moscow’s Red Square in 1982 (open Tuesday to Thursday and Saturdays; closed Sunday, Monday and Fridays – admission free). Other than his respiratory and excretory functions, Lauri offers no signs of life. Strangely, he is visited almost as often as the late Vladmir Lenin. People wanted to talk to him, even though he shows no ability to reply.

The circumstances surrounding Lauri’s vegetative state – the choice of meal at the beginning is deliberate – become apparent throughout the course of the film. The village policeman updates Elsa on the course of the investigation. Elsa’s husband takes no interest in it, although at one point, hunters – as the only gun owners in the region – are implicated in the shooting. It turns out that Dad had a frosty relationship with his son; he could never bond with him, leaving Elsa to raise him.

Lauri, as it turned out, was quite flush with cash. He removed 80,000 Euro from his account before he died. Half of it, we discover, was loaned to a friend in the construction business whose money problems threaten to sink him. We wonder what happened to the other half.

Lauri’s boss, the school principal, Aarne (Jaak Prints) pops up every so often to see Lauri, with a bunch of flowers – sometimes a single one – in his hand. He and Lauri are having a passionate but unlikely affair; the film fairly explodes into a sex scene with jump cuts. Elsa resembles Freda Dowie, who played the abused mother in Terence Davies seminal ‘Distant Voices, Still Lives’ (1988). She is quiet, tentative, likely to cut herself whilst slicing vegetables (maybe that’s why she boiled the potato whole). Lauri’s other visitors include his erstwhile business partner, some school children who want him to recover in time for a hiking trip, his young girlfriend, who shares his bed at one point, clinging to his comatose body as if he were just asleep and, eventually, Lauri’s dad.

Kðussar was told by an expert that only three films have ever depicted a comatose state realistically; hers is apparently the fourth (something for the poster). ‘Ema’ was something of a domestic hit, though I must have misheard the claimed 200,000 admissions – Estonia only has a population of 1.3 million and it is unlikely that 15% of the population went to see it. She doesn’t impose a style on the film. Although it has the plot elements of a film noir, it maintains a moderately picturesque setting, with attention paid to cleaning the lounge and pulling up weeds. Elsa too becomes obsessed by the missing 40,000 Euro; Lauri’s room is searched – including by his girlfriend – multiple times.

Humour, such as it is, comes from a slightly batty home help, who tends to Lauri whilst recovering from a hangover and from the over-eager Aarne, with his Hawaiian style shirt. The film is about repressed emotions but doesn’t at any point provide an emotional release. Instead, we get a late movie twist that asks us to re-think the behaviour that we have witnessed.

Apparently, the village in ‘Ema’ is typically Estonian. At the post screening question and answer session, Kðussar likened it to Emil Braginsky and Eldar Ryazonov’s ‘The Irony of Fate’ (otherwise known as ‘Enjoy Your Bath’) (1976) in which a man ends up in an apartment identical to his own that belongs to a young woman who finds him in her bed; one of the jokes is that his key fits exactly. The film is about the inability to create a home filled with love; those who don’t love have homes, those who do can’t afford them. So the film – at a real stretch – explores Estonia’s attempt to recover from the 2004 to 2009 housing bubble, when construction declined after 2008. So for a hit movie (moderately speaking) ‘Ema’ doesn’t scream ‘invest in Estonia’, but it does suggest that Estonian cinema might be worth a closer look.

Reviewed at Nordic-Baltic Film Festival, Regent Street Cinema, Central London, Tuesday 6 December 2016, 18:00 screening with assorted Nordic fare