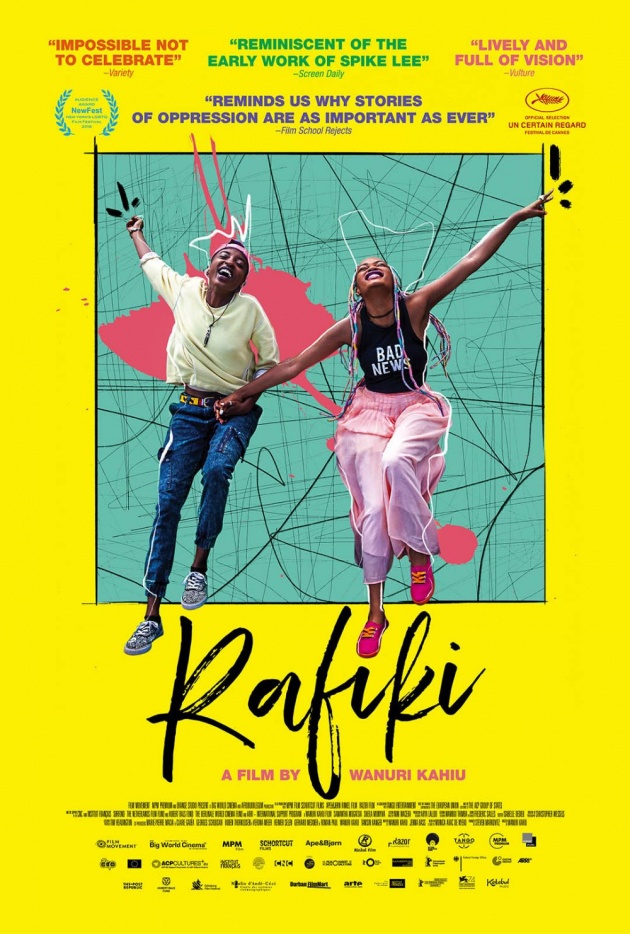

Pictured: Kena (Samantha Mugatsia) and Ziki (Sheila Munyiva) pay only partial attention to the pastor in 'Rafiki' (friend), a Nairobi-set love story directed by Wanuri Kahiu. Still courtesy of MPM Premium / Big World Cinema

Sometimes it is enough for a film to be a catalyst. Responding to a Twitter question, ‘what was the happiest day of your life,’ one Kenyan woman wrote ‘watching Rafiki with my mother and coming out’. Films should make people examine the important issues in their lives, be it homophobia, climate change or social inequality. To talk through an issue is to test the validity of a preconception, to understand, if not always sympathise with opposing points of view. Minds are changed not by a film preaching a particular message, but by stimulating a debate.

The short story that inspired Rafiki, ‘Jambula Tree’ won the Caine Prize for its Ugandan author Monica Arac de Nyeko in 2007. It describes from a first person perspective the love felt between two schoolgirls, Anyango (the narrator) and Sanyu. The real story is why Arac de Nyeko has not been published since.

In adapting ‘Jambula Tree', director Wanuri Kahiu, who co-wrote the screenplay with Jenna Bass, relocates the story to contemporary Nairobi, where helicopters fly overhead and a skyscraper or two can be seen in the distance. Her protagonist, Kena (Samantha Mugatsia) is a schoolgirl awaiting her exam results. Her father, John (Jimmy Gathu) is an aspiring politician who has his own kiosk and is standing for election. He has re-married; his young wife is expecting a son.

We first see Kena, named, we surmise, after Kenya (the country) itself, without the ‘y’ chromosome, on her skateboard. She heads to her friend, Blacksta (Neville Misati) who is saying goodbye to another woman, who we later learn works at a cafe. They are friends but not romantically involved – their scenes clunk with a lack of authenticity. Near her father’s shop, Kena notices three girls practising a dance routine. One of them is Ziki (Sheila Munyiva), a young woman with long decorated braids. No man bothers Ziki and her friends. Ziki is the daughter of another local politician, Peter Okemi, so-called ‘man of action’.

Kena only discovers by accident that a sibling is one the way. Her father wants to talk to her but (inexplicably) Kena does not have time. She plays football with the local boys and rides her board, whilst never escaping the notice of the community gossip, Mama Atim (Muthoni Gathecha). ‘She [Atim] is a terrible gossip but tells the truth,’ one character says.

The film has a number of recurrent visual tropes. There are numerous shots of washing lines filled with clothes. When it rains, suddenly and sharply, the washing is left to get wet again. Kena is repeatedly seen stopping on her skateboard – the actress Mugatsia has a skateboard double. Characters are also viewed through hanging drapes or beaded curtains; they are obscured to illustrate hidden behaviour.

When Ziki and her friends deface John’s election posters, Kena chases after them, on foot rather than on her board. Ziki notices Kena looking at her. ‘We should go for a drink’, Ziki suggests. They end up at Mama Atim’s cafe, where an openly gay man is mocked by the locals. Kena asks to leave.

They end up in an abandoned van. Kena and Ziki stare at each other. Then they kiss. The soundtrack emphasises the smacking of lips – no music is laid over the scene. This is the first of several kissing scenes.

In the most expressive piece of editing, Kahiu cuts back and forth from Kena and Ziki having a snack to Kena lying on top of Ziki and touching her (fully clothed) breast. Kahiu is mindful of censorship but she does not offer a series of metaphorical equivalences, such as the women biting into watermelon.

There are numerous scenes at church. The pastor praises both Kena and Ziki’s fathers, the former for his generosity. Kena’s mother confronts John. Why didn’t he tell her about the baby? The would-be politician is lost for words. Later, Ziki tries to hold Kena’s hand at church, but Kena refuses.

Pictured: Kena (Samantha Mugatsia) and Ziki (Sheila Munyiva) have fun in a pedalo in 'Rafiki', a Kenyan romance directed by Wanuri Kahiu. Still courtesy of MPM Premium / Big World Cinema

At one point, Kena is playing football with local boys and scores a goal. Ziki and her friends ask to join her. The boys are sceptical but, speaking Swahili, Kena entreats her fellow players to allow them to take part.

Both Kena and Ziki are in the same class. Kena finds out her exam results from Ziki. Straight As. Kena wants to be a nurse. ‘Why not a doctor?’ asks Ziki. Kena is encouraged to expand her horizons; she is clever enough.

The time they spend together feels constrained. ‘I wish we could be real,’ Kena sighs. She wishes they could go on a real date. They do – sort of. They end up in a club where their faces are daubed with neon glowing paint. It’s a strong look.

Ziki’s friends notice Kena’s attention. Elizabeth (Mellen Aura) shoves her. ‘Stay away,’ Kena is told. The church scene leads to an act of violence. Kena and Ziki are followed to the van. A crowd ushers them out. Ziki is beaten and kicked. We hear the ripping of cloth. Kena is also hurt. Both girls end up at the police station, where the two officers at the front desk, OII 236 and OII 234 gloat. Ziki’s father collects her. Kena just walks out, unrestrained.

Pictured: The forbidden kiss. Ziki (Sheila Munyiva) and Kena (Samantha Mugatsia) in 'Rafiki', a love story directed by Wanuri Kahiu. Still courtesy of MPM Premium / Big World Cinema

The two girls are forbidden from seeing each other. Ziki receives a particularly cruel punishment from her family. The final scene offers some hope.

Kahiu succeeded in overturning a ban to allow the film to be screened in Kenya for seven days to allow an Oscar qualifying run. In the end the film wasn’t put forward as Kenya’s official entry for Best Foreign Language Film. The male characters are sketchily written, but the dearth of dialogue leads to one good scene, when the gay man whose cause Kena had taken up sits down next to her. They are kindred spirits.

The film doesn’t put you in Kena’s head. We don’t feel her aching desire. There is a strong scene in which the pastor tries to remove the ‘evil spirit’ from within her. John’s election posters are also defaced.

The title Rafiki means ‘friend’ in Swahili. The film does not offer a fair examination of friendship. We never get to see what Ziki wants, how she and Kena could have a loving relationship of equals. The film succeeds best as an expression of possibility rather than a complete and compelling drama.