Pictured: Ifrah Ahmed (Aja Naomi King) in 'A Girl from Mogadishu', Irish writer-director Mary McGuckian's fact-based retelling of Ifrah's journey from victim to advocate. Still courtesy of Seamus Murphy for Pembridge Film Productions Limited All Rights Reserved

‘If you like my film, shout about it on social media. If you don’t, use your breath to cool your toast’ (Mary McGuckian, Edinburgh International Film Festival, Friday 28 June 2019)

Writer-director Mary McGuckian (born 1965) is possibly the worst reviewed filmmaker working in Irish cinema today – at least as far the website imdb.com is concerned. With a career spanning twenty-five years – her debut, Words Upon The Window Pane was released in 1994 – she has no difficulty attracting major talent to star in her films, having worked with Robert de Niro, F. Murray Abraham, Kathy Bates, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Malcolm McDowell, Andie MacDowell, Donald Sutherland, Geraldine Chaplin, Kerry Fox, Alanis Morissette, Amanda Plummer, Richard Harris, Samantha Morton, Stephen Fry and Larry Mullen Jr of U2. She even cast director Jim Sheridan as the King of Spain in 2004’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey. Many of her films are comedies - 2005’s Rag Tale, 2008’s Inconceivable and 2010’s The Making of Plus One - in which she devises the script with the actors. Many of her cast members return for second helpings, step forward Canadian actor Lothaire Bluteau and cinema’s best John Lennon, Ian Hart.

McGuckian was apparently warned off tackling female genital mutilation in her eleventh film as director, A Girl from Mogadishu, adapted from the testimony of Somalian refugee turned FGM activist, Ifrah Ahmed. Apparently, the subject is ‘career-ending’. But McGuckian’s career wasn’t ended by savage reviews and poor box-office returns for The Bridge of San Luis Rey, which co-starred De Niro, Bates and Abraham in an adaptation of Thornton Wilder’s novel. She has raised the bar. Her response was to use her connections with the acting world (she was married to John Lynch until 2012) to go for actor-generated content.

McGuckian tackles interesting and diverse subjects, but the sense I get is that she hasn’t developed a style that brings them to life. In a common understanding of cinematic storytelling, directors seek to involve the audience in a story through a protagonist. You side with them as they overcome obstacles. I don’t think McGuckian believes in audience surrogates: she wants to draw your attention to the bigger picture. There is a narrative rupture in A Girl from Mogadishu as the principle viewpoint character Ifrah (Aja Naomi King) is displaced by a documentary style account of how she became a spokesperson for a huge cause and hob-nobbed with Irish politicians. As the screen Ifrah delivers speech after impassioned speech and Labour leader Michael D. Higgins (Niall Buggy) believes she is just the sort of cause he should support to get him elected as President of Ireland, McGuckian distances us from the individual. Given that Ifrah had been ‘cut’ (the euphemism for FGM) at aged nine, we don’t find out how this affected her. What we see instead is a woman who gains pleasure from applause. At no point is there a frank discussion as to what female genital mutilation actually is.

A quick visit to the NHS UK website will tell you more about FGM than McGuckian’s coy movie. It is referred to in various languages as ‘sunna’, ‘gudniin’, ‘tahur’, ‘megrez’ and ‘khitan’. It serves no medical purpose. There are four types of FGM (or female genital cutting): clitoridectomy; excision; infibulation; and procedures lumped together as pricking, piercing, cutting, scraping or burning the area. It is practiced in thirty countries, predominantly in western, eastern and north eastern Africa, but also by immigrant communities in North America and Europe. The procedure has lasting effects on the women who are cut. Depending on what type of cutting is done, women experience one or more of the following: constant pain; pain and difficulty having sex; repeated infections which can lead to infertility; bleeding, cysts and abscesses; incontinence (problems urinating, or holding in urine); psychological effects including depression, flashbacks and self-harm; and problems during labour and childbirth, which could threaten the lives of both mother and baby.

The website globalcitizen.org lists eight countries where FGM has affected over 80% of women: Somalia, where it is most prevalent, affecting 98% of the female population; Guinea (97% of women affected); Djibouti (93% of women affected); Sierra Leone (90% of women affected); Mali (89% of women affected); Egypt, the country with the largest population of the eight (95.7 million) and therefore with the biggest problem (87% of women affected); Sudan (87% of women affected) and Eritrea (83% of women affected). The United Nations General Assembly voted unanimously in 2012 for female genital mutilation to end. Progress towards the goal is slow, though in 2014, UNICEF reported that 8,000 communities across Africa had agreed to give up the practice. Ifrah herself is working towards a target through public advocacy of ending the practice by 2030. In Egypt, unlike in many of other countries, it is carried out by trained medical professions, giving it the appearance of legitimacy.

Why is it practiced? Reasons vary, but essentially it is an attempt to control the sexual behaviour of women. According to anecdotal evidence, in many communities, it is believed to reduce a woman’s libido and therefore help her resist ‘illicit’ sexual acts. There is also the belief that women’s genitalia are ‘unfeminine, ugly or unclean’. (Sarah Boseley, The Guardian, 6 February 2014). In some instances, a woman’s vagina is partially sewn up. In labour and often without anaesthetic, the stitches have to be removed before the woman can deliver a child.

A community based approach would appear to be the best way to end the practice. However, addressing the underlying causes, for example, superstition, and a ‘lack of trust’ of women, is a considerable challenge. Arguably, FGM is part of a series of practices that enable communities to marry off women and turn them into men’s property. Whatever the advocates say, eleven years [from 2019 to 2030] seems an awfully short time to achieve that level of behaviour change.

To underline this point, it is worth looking at those eight countries where FGM is most prevalent:

Somalia: In urban areas, Somali women are more likely to be heads of households than in rural areas, but traditionally have not been allowed to make financial decisions or own property

Guinea: Only 12% of women own a house (source: OECD gender index)

Djibouti: According to article 31 of the Family Code the wife must also “respect the prerogatives of the husband, as head of the family, and owes him obedience in the interest of the family... women should be confined to the private sphere where they ensure the well-being of home and family.” (Source: OECD gender index)

Sierra Leone: Whilst women constitute the majority of the agricultural workforce, they have never had full access or control of land or property (source: Human Rights Defenders, Sierra Leone ‘Joint Parallel Report to the United Nations Human Rights Committee’, March 2014)

Mali: Despite statutory support for women’s equal rights to obtain title to land, women in Mali do not actually enjoy equal land rights. The vast majority of Malians access land either on the basis of customary law, religious law or some combination of the two. Under these systems, primary rights to land are passed from men to their male heirs. (Source: Focus on Land in Africa)

Egypt: ‘According to Egyptian laws, women can own, inherit, and independently use land and property. While no longer prevalent, it is still preferable practice for male heirs to own land so that outsiders cannot inherit through marriage’ (Source: Refworld, ‘Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa’)

Sudan: ‘Similarly in North Sudan, notwithstanding that women and men are treated equally under North Sudanese land law, in rural areas land issues are generally dealt with under customary laws which are rooted in patriarchy. Land tends to be owned and controlled by the male head of household, regardless of who lives on or contributes to working the land.’ (Source: World Bank /Trust Law Connect report, ‘Women and Land Rights: Legal Barriers Impede Women’s Access to Resources’)

Eritrea: ‘The distribution of land is in most cases handled by land distribution committees at the village level. The National Union of Eritrean Women reports that negative attitudes of local authorities towards women’s land rights prevents the principle of gender equality being implemented in practice.’ (Source: Report by the Global Initiative for Social, Economic and Cultural Rights, ‘Parallel Report to the United Nations Committee on the elimination of discrimination against women: Eritrea’, March 2015)

There is absolutely a link between FGM and the proprietal disenfranchisement (English: ‘inability to own property’) of these women.

This returns me finally to the movie itself. You will be hard pressed to feel something. This because McGuckian has contradictory impulses: to make a plea for the end of female genital mutilation whilst showing a character living a fulfilling life in spite of it. McGuckian is going for uplift but she is almost too polite to show the impact of FGM on Ifrah. ‘Be the voice – not the victim’ is the film’s strap line. But I think McGuckian had an artistic obligation to illustrate the horror of FGM, not just in the act, which is shown roughly half way through, but in the aftermath. In case, uplift comes from catharsis; McGuckian puts the horse before catharsis.

The ‘idyllic’ opening set in 1999, albeit with military jets soaring overhead shows Ifrah as a child receiving a necklace. The image is distorted with the background blurred; Michael Lavelle’s cinematography suggests an uncertain sun-dappled happiness. This is the day that Ifrah is cut, but McGuckian withholds this information. Cut to several years later. The bloody civil war is coming to an end. Ifrah, married to a fifty year old, has fled her husband. She tries to find her father amongst the general carnage. In the course of her search, she is surrounded by soldiers and raped – McGuckian tackles this scene sensitively. Ifrah eventually finds her father, but he sends her away. ‘It was the last time I would see him,’ Ifrah’s voiceover informs us. With no prospect of staying in Somalia, Ifrah flees to Ethiopia. She is sent money by an aunt in Minnesota, where a Somali Diaspora is established, though in Ifrah’s aunt’s case, illegally. Ifrah attempts to join her.

Pictured: Ifrah Ahmed (Aja Naomi King) in a scene from 'A Girl from Mogadishu' a drama about female genital mutilation written and directed by Mary McGuckian. Still courtesy of Irish Film Board / Pembridge Films

Pictured: Ifrah Ahmed (Aja Naomi King) in a scene from 'A Girl from Mogadishu' a drama about female genital mutilation written and directed by Mary McGuckian. Still courtesy of Irish Film Board / Pembridge Films

The film has some tense moments early on as Ifrah is forced to hang on to the top of a bus. On the long journey, the bus is stopped as militia demand that the women separate from the men and all passengers should surrender their papers. The identity documents are then thrown into a fire. The militia then demand $100 for each passenger without papers, which is paid reluctantly. (Would a bus driver really have that much cash?) Ifrah watches from the top of the bus, hidden among the luggage. She fears the worst. Ifrah is almost visible but the bus is allowed to continue on its uncertain journey.

Eventually, Ifrah has a seat inside the bus. A man takes an interest in her. The driver advises her not to go with him as he is a people trafficker responsible for recruiting domestic servants sent, ostensibly as slaves, to the Middle East. Instead, Ifrah stays with a family in Ethiopia until a contact (Barkhad Abdi, best known for playing a Somali pirate in Captain Phillips) gets her out of the country.

In these early scenes, McGuckian’s recreates Ifrah’s responses to the experience of air travel; her reluctance to consume airline food, though the orange juice is tolerable. To her surprise she ends up in Ireland. Travelling with her in a taxi, the smuggler drops her off at a police station in Dublin and asks her to claim asylum. Ifrah does so reluctantly.

McGuckian makes pains to show that Ifrah’s application was processed fairly. She is assigned a social worker (Pauline McLynn, best known for playing Mrs Doyle in the TV sitcom, Father Ted) and has a translator to help. In the film’s best scene, at a refugee hostel, Ifrah is given cornflakes to eat, which dribble out of her mouth. A hostel worker laughs at her. Ifrah throws the bowl at him. This gets her barred. It is the only scene where Ifrah’s sense of herself kicks in.

Then there’s the medical inspection. A male doctor is brought in to check her ‘downstairs area’ and gets a shock. This discovery transforms the way Ifrah is treated. She learns English. There is a narrative leap of about five years. Ifrah is suddenly a passionate advocate against female genital mutilation and has her cause taken up by the then (Irish) Labour Party leader, Higgins.

McGuckian milks some comedy out of Ifrah being refused entry to the Irish Parliament, until Higgins turns up, then getting a whole group of Somalis into an event in which then US President Barack Obama is the guest speaker. McGuckian integrates actual footage of President Obama with the screen Ifrah and her activists holding up placards saying ‘yes, we can end FGM’.

Ifrah eventually speaks at the European Parliament and, it is implied, helps Higgins get elected as Irish President. The security guard who earlier scowled at her is happy to see her, having earlier been mildly threatened by Higgins. The climax focuses on Ifrah returning to Somalia to confront her grandmother, to ask why she allowed Ifrah to be cut.

There is a wobbly scene in which her smuggler reappears to warn Ifrah against her campaign. She also reads hostile comments on her Facebook page. She is (unexpectedly) reunited with her father, which gives the film its closure.

So much of the last part of the film feels like virtue signalling. Ifrah’s psychology and her non-campaigning life do not get a look in. The film doesn’t have an emotional through-line, which results in the viewer being unengaged.

Higgins’ first act as President is to criminalise female genital mutilation in Ireland. Ifrah Ahmed was directly responsible for that. We don’t get a sense of what this achieved. The bigger struggle – how to get communities wedded for myriad reasons to FGM to end it – isn’t even addressed. Arguably, that is a better, more relevant story to tell.

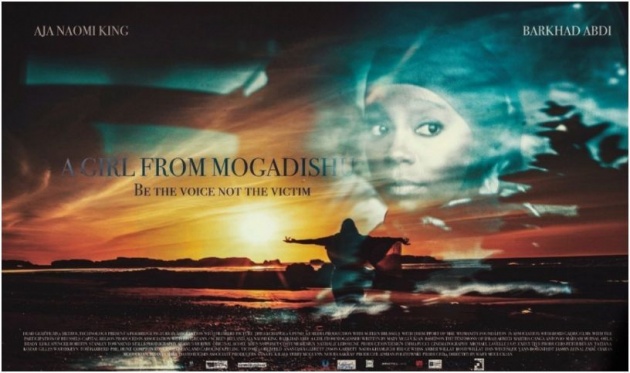

Pictured: The pre-release film poster for 'A Girl from Mogadishu'. Courtesy of Irish Film Board / Pembridge Films

Pictured: The pre-release film poster for 'A Girl from Mogadishu'. Courtesy of Irish Film Board / Pembridge Films

The films that change social attitudes do so first by shocking us, then by empowering us with a deeper sense of injustice that compels us to act. As a campaigning tool, A Girl from Mogadishu is fairly limited.

There is another story in Ifrah’s life that McGuckian could have told, how in 2018, Ifrah helped to secure the first prosecution for committing FGM in Somalia, following the death of a ten year old girl, Deeqa, who was sent to a traditional cutter in Galmudug state. However, filming, which started in 2017, had already been completed. This does at least give McGuckian or another filmmaker the subject for a sequel. For all its virtuous intent, it is hard to see A Girl from Mogadishu resonating with mass audiences.

Reviewed at Edinbugh International Film Festival, Friday 28 June, 20:45 screening, Odeon Lothian Road, Screen Four

Trailer: not available