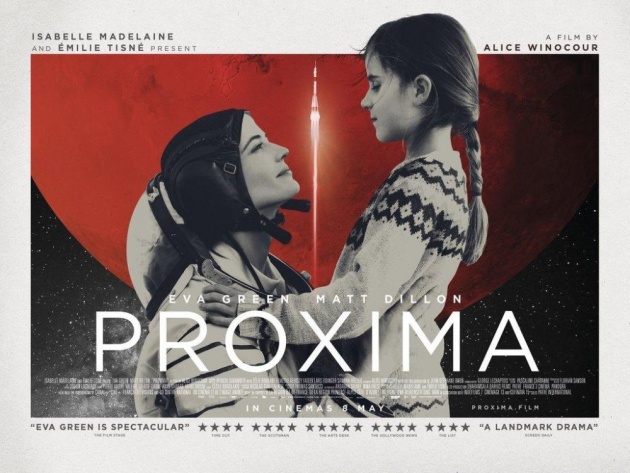

Pictured: Astronaut Sarah Loreau (Eva Green) says 'au revoir' to her eight-year-old daughter, Stella (Zélie Boulant-Lemesle) in the French mother-daughter drama, 'Proxima', co-written and directed by Alice Winocour. Still: © Dharamsala – Darius Films – Pathé Films – France 3 Cinéma

Most films about space travel tend to be high-concept action adventures. In director Michael Bay’s 1998 film Armageddon, starring Bruce Willis and Ben Affleck, for instance, a team of oil drillers are sent into space to neutralise an asteroid that threatens to devastate the planet. By contrast, Alice Winocour’s third film as director, Proxima, shot on location in actual space training facilities, is a much smaller, more intimate affair.

Co-written by Jean-Stéphane Bron, with whom Winocour collaborated on her previous film, the PTSD bodyguard thriller, Disorder, it shows French astronaut Sarah Loreau (Eva Green) in her final preparations for departure from Earth for a minimum one-year mission to Mars. She could not be more excited. However, she is leaving behind her young daughter, Stella (Zélie Boulant-Lemesle). Stella is a sullen child, having been diagnosed with dyslexia, dyscalculia and dysorthographia, which means she has difficulty reading, understanding mathematics and writing. Her German father, Sarah’s ex-husband Thomas (Lars Eidinger), the kind of guy who writes complex calculations in red ink on his kitchen cabinet where others might remind themselves to fetch cereal, thinks it is ironic that Stella has trouble with mathematics. Nevertheless, Sarah has given him a fait accompli – he must look after her while she is gone. That means that Stella and the family cat, Laika, must move in with him. Stella is worried: but what about their two newts? Sarah takes Stella to the river to set them free, saving goodbye to each one in turn. Like Stella, we search for the newts through the muddy water. There is one and, look, there is the other.

The film begins with a conversation between Sarah and Stella, heard over the film’s titles. The former has spent a long time explaining her departure to the latter. Winocour cuts from this cute conversation to shots of Sarah training, running on a vertical treadmill and practising the use of an electronic arm. Green, who has had a long career in genre films of the running, jumping and turning-into-animals kind – her credits include Casino Royale, 300: Rise of an Empire and The Golden Compass – meets the physical demands of the role without breaking into a sweat. But Winocour begins the film with a mother-daughter conversation in order to prioritise the relationship over the allure of space travel. This is not a film where we cannot wait to join Sarah in her adventures in space – basically a long ride in total darkness with no in-flight entertainment. This is a film about accommodation.

Pictured: ' What do you know about my core skills?' Sarah (Eva Green) faces off against fellow astronaut, Mike Shannon (Matt Dillon) in the mother-daughter drama, 'Proxima', co-written and directed by Alice Winocour. Still © Dharamsala – Darius Films – Pathé Films – France 3 Cinéma

‘There’s no such thing as a perfect astronaut,’ says American astronaut Mike Shannon (Matt Dillon) reassuringly. ‘There’s no such thing as a perfect mother either.’ Dillon is not the most sympathetic screen presence. We last saw him as a serial killer in Lars Von Trier’s The House That Jack Built. Dillon has a cold, steady gaze, great for playing card sharps or killers. His face has not aged since I first saw him in the film, My Bodyguard in the early 1980s. I do not think Dillon applies any special facial cream. It is like he developed a persona so cold that his features froze. Then there is his gravelly voice. Back in the 1980s, it seemed old before its time. He speaks as if to warn. He cannot tell jokes. When Mike introduces Sarah at a press conference, he says that it will be great to have a French woman in the space station because they are such great cooks. Sarah glowers at him, suppressing her embarrassment. With a face that does not age, Dillon is great at playing characters out of synch. He is also insincere. Most major movie stars spend their downtime on a farm in the open air (think Kevin Costner and Harrison Ford); Dillon appears to spend his in front of a mirror.

At the barbecue that follows the press conference, Sarah is subjected to Mike’s second barb at her nationality. ‘I guess you want this hot dog medium rare,’ he says, ‘though I wouldn’t recommend it.’ Sarah is more concerned about Stella, who refuses to play with Mike’s kids. Whilst her daughter is around, Sarah cannot stop being a mother.

Sarah’s home life is precarious. There is an early scene where Laika the cat dips her head into a glass jug on the kitchen table to reach the water at the bottom; we fear for the jug. Fortunately, Sarah arrives just in time to carry Laika to her food bowl. (Does not she know the cat is thirsty?) When Stella arrives at her father’s apartment, she and Laika head for the balcony. Laika sticks her head through the bars, sharing Stella’s curiosity; I worried whether Laika might get stuck. Sarah, Thomas and Stella go out for a meal. Sarah explains how she has been advised to develop a social media profile. Thomas says it is easy: take a picture of a meal and add a caption ‘family time, hashtag yum yum!’ Sarah is not the hashtag type. Nevertheless, Stella wants to take a photo.

Pictured: 'Where's Mutti? There she is!' Thomas (Lars Eidinger) in a scene from 'Proxima', a film co-written and directed by Alice Winocour. Still © Dharamsala – Darius Films – Pathé Films – France 3 Cinéma

Having arrived at the facility one hour’s drive from Moscow (we see a blue facsimile of the Winter Palace outside the window), Sarah’s training requires her to wear a space suit, go underwater and practice moving on the outside of a mock capsule. Generally sceptical about having a woman crew member, Mike is keen to reduce her training schedule. ‘It is no reflection on your core skills,’ he adds. ‘What do you know about my core skills?’ Sarah asks. The Russian cosmonaut travelling with them, Anton Ochieskiy (Aleksey Fateev) tries to act as peacemaker, but no avail. Sarah swallows her vodka quickly and leaves. (General rule: do not get comfortable with a guy who plays Camille Saint Saens’ ‘Dance Macabre’ in his office.) Nevertheless, in an exercise, Mike plays unconscious and Sarah moves his limp body to the airlock within the allotted time, though the guy telling her how much time she has left is not honest – thirty seconds takes one-third of that according to his defective stopwatch. Team building between the trio takes time too. During a camping exercise in the long grass, Anton tells Sarah that he is worried that his mother might not be alive when he gets back. Sarah gives him a sympathetic look. Mike offers no such reassurance. However, when Mike twists his ankle, Anton and Sarah lie on his behalf. There is an unspoken agreement: they will not give the Space Agencies (European and International) a reason to deselect any of them. This manifests itself when Sarah faints in the water and sinks to the bottom of the tank. She is rescued, but this time Mike lies on her behalf: ‘she’s fine.’

Meanwhile, Sarah starts to lose touch with her daughter. She is surprised to hear from Wendy (Sandra Hüller), the European Space Agency’s family liaison officer, that Stella is interested in a boy who has a deaf brother and does not know how to speak with him. We see the shock in Sarah’s face as she takes a phone call: her daughter is developing without her. It is moments like this that Winocour does exceptionally well, showing the emotional impact of Sarah’s trade-off, a career in exchange for motherhood.

Stella spies on the two young boys using her father’s telescope. They see her and rush to her apartment: ‘come out and play’. Stella stands with her back to the door, listening to their cries, thrilled but anxious.

Sarah watches video footage of Stella learning to ride a bike, something that makes her both thrilled and anxious. Stella visits her at the training facility, accompanied by Wendy. ‘She almost missed the plane from Frankfurt,’ Wendy explains. After a brief time together in the pool, Sarah takes Stella to her briefing. Stella is bored. She crawls under the table to cling to her mother and then disappears. Sarah leaves the briefing to find her – she is anxious, not thrilled. Stella is found in the woods. ‘A briefing is not a place for a young girl,’ Mike tells Sarah. Incidentally, his only family anecdote is about his two boys using the outdoor pool in late autumn. ‘Who can deny climate change?’ he asks, which in the context of his preceding dialogue is a very un-Matt Dillon thing to say.

Stella is angry with her mother, who in turn oversleeps. Stella and Wendy leave Sarah a note. Sarah is required to sign a form to consent to not being told should something happen to Stella in her absence; Sarah is reluctant to cut the cord. She marvels at video footage of her daughter’s room, with pictures of horses on the wall. She is horrified that Stella has broken her arm after an accident with her bicycle and now has a pink plaster cast. ‘All my friends signed it,’ she explains. Stella the lonely, sullen child, in danger of being put back a year in school, has friends? Early we are told no one in her new school would talk to her. When Stella later tells her mother that she has an ‘A’ in Maths, Sarah scolds her, ‘don’t lie’.

The finale takes place at Star City, from where the Proxima Mars Mission rocket will be launched. By this time Mike and Sarah have bonded over a trip to a local supermarket, where Sarah purchased a large teddy bear for her daughter and Mike asks the checkout lady who sells more fridge magnets: Mike or Sarah? ‘The same,’ the checkout girl says diplomatically. This time, at Star City where Sarah is due to go into quarantine, Stella has missed the plane. Sarah promised to show her the rocket. When Stella arrives (with Thomas and Wendy), Sarah can only talk to her behind plate glass. However, a promise is a promise: Sarah breaks quarantine to show her daughter (who previously identified with the wolf but now likes horses) the rocket. ‘What are you doing?’ Thomas asks sceptically when Sarah turns up at their door. Afterwards, Sarah showers with disinfectant body soap that looks like brown sauce. She boards the rocket as if nothing had happened.

Even before Covid-19, this action looks reckless, but Sarah wanted to show Stella how much she means to her. The final image of the film shows Stella staring out of the bus window, seeing a group of wild horses racing in a pack together. It is what we do as a collective that is important.

On first viewing (I have seen the film twice), I was disappointed that we did not see Sarah in space. Space rockets are so associated with a certain type of cinema that I wanted the pay off that we normally expect. However, Winocour successfully subverts our expectations and tells an extraordinary story that we do not normally see, about the accommodation of ambition in a strong mother-daughter relationship, where both grow as a result.

Reviewed at Cineworld Wood Green, Screen Ten, North London, Friday 7 August 2020 (first viewing: Toronto Light Box, Toronto, Canada, Friday 13 September 2019, 13:00 screening)