Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (Old Persian: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Kūruš; New Persian: کوروش بُزُرگ Kurosh-e Bozorg ; c. 600 or 576 – 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great and also called Cyrus the Elder by the Greeks, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Under his rule, the empire embraced all the previous civilized states of the ancient Near East, expanded vastly and eventually conquered most of Southwest Asia and much of Central Asia and the Caucasus. From the Mediterranean Sea and Hellespont in the west to theIndus River in the east, Cyrus the Great created the largest empire the world had yet seen. Under his successors, the empire eventually stretched from parts of the Balkans (Bulgaria-Pannonia) and Thrace-Macedonia in the west, to the Indus Valley in the east. His regal titles in full were The Great King, King of Persia, King of Anshan, King of Media, King of Babylon, King of Sumer and Akkad, and King of the Four Corners of the World.

Kūruš; New Persian: کوروش بُزُرگ Kurosh-e Bozorg ; c. 600 or 576 – 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great and also called Cyrus the Elder by the Greeks, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Under his rule, the empire embraced all the previous civilized states of the ancient Near East, expanded vastly and eventually conquered most of Southwest Asia and much of Central Asia and the Caucasus. From the Mediterranean Sea and Hellespont in the west to theIndus River in the east, Cyrus the Great created the largest empire the world had yet seen. Under his successors, the empire eventually stretched from parts of the Balkans (Bulgaria-Pannonia) and Thrace-Macedonia in the west, to the Indus Valley in the east. His regal titles in full were The Great King, King of Persia, King of Anshan, King of Media, King of Babylon, King of Sumer and Akkad, and King of the Four Corners of the World.

The reign of Cyrus the Great lasted between 29 and 31 years. Cyrus built his empire by conquering first the Median Empire, then the Lydian Empire and eventually the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Either before or after Babylon, he led an expedition into central Asia, which resulted in major campaigns that were described as having brought "into subjection every nation without exception".Cyrus did not venture into Egypt, as he himself died in battle, fighting theMassagetae along the Syr Darya in December 530 BC. He was succeeded by his son, Cambyses II, who managed to add to the empire by conquering Egypt, Nubia, and Cyrenaica during his short rule.

Cyrus the Great respected the customs and religions of the lands he conquered. It is said that in universal history, the role of the Achaemenid Empire founded by Cyrus lies in its very successful model for centralized administration and establishing a government working to the advantage and profit of its subjects. In fact, the administration of the empire through satrapsand the vital principle of forming a government at Pasargadae were the works of Cyrus. What is sometimes referred to as the Edict of Restoration (actually two edicts) described in the Bible as being made by Cyrus the Great left a lasting legacy on the Jewish religion, where, because of his policies in Babylonia, he is referred to by the Jewish Bible as Messiah (lit. "His anointed one") (Isaiah 45:1), and is the only non-Jew to be called so:

So said the Lord to His anointed one, to Cyrus

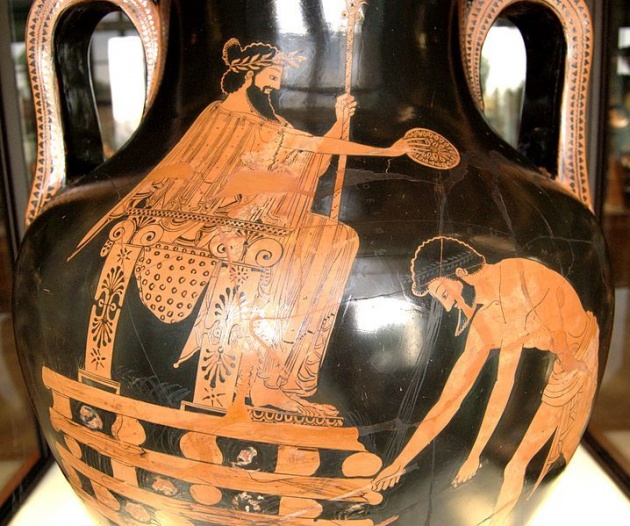

Cyrus the Great is also well recognized for his achievements in human rights,politics, and military strategy, as well as his influence on both Eastern andWestern civilizations. Having originated from Persis, roughly corresponding to the modern Iranian province of Fars, Cyrus has played a crucial role in defining the national identity of modern Iran. Cyrus and, indeed, the Achaemenid influence in the ancient world also extended as far as Athens, where many Athenians adopted aspects of the Achaemenid Persian culture as their own, in a reciprocal cultural exchange.

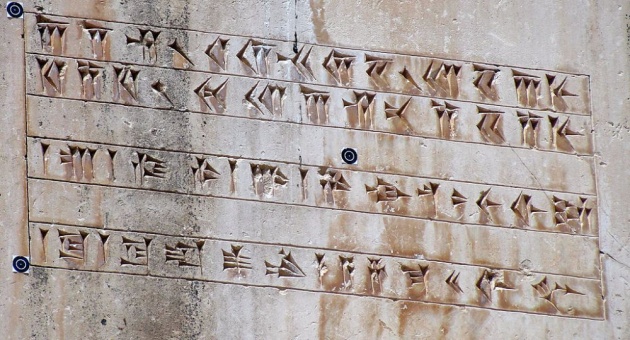

In the 1970s, the Shah of Iran Mohammad Reza Pahlavi identified his famous proclamation inscribed onto Cyrus Cylinder as the oldest known declaration ofhuman rights, and the Cylinder has since been popularized as such. This view has been criticized by some historians as a misunderstanding of the Cylinder's generic nature as a traditional statement that new monarchs make at the beginning of their reign.

Background

Etymology

The name Cyrus is a Latinized form derived from a Greek form of the Old PersianKūruš. The name and its meaning has been recorded in ancient inscriptions in different languages. The ancient Greek historians Ctesias and Plutarch noted that Cyrus was named from Kuros, the Sun, a concept which has been interpreted as meaning "like the Sun" (Khurvash) by noting its relation to the Persian noun for sun,khor, while using -vash as a suffix of likeness. This may also point to a fascinating relationship to the mythological "first king" of Persia, Jamshid, whose name also incorporates the element "sun" ("shid").

Karl Hoffmann has suggested a translation based on the meaning of an Indo-European-root "to humiliate" and accordingly "Cyrus" means "humiliator of the enemy in verbal contest". In the Persian language and especially in Iran, Cyrus's name is spelled as کوروش [kʰuːˈɾoʃ]. In the Bible, he is known as Koresh (Hebrew: כורש).

Dynastic history

The Persian domination and kingdom in the Iranian plateau started by an extension of the Achaemenid dynasty, who expanded their earlier domination possibly from the 9th century BC onward. The eponymous founder of this dynasty was Achaemenes (from Old Persian Haxāmaniš). Achaemenids are "descendants of Achaemenes" as Darius the Great, the ninth king of the dynasty, traces his genealogy to him and declares "for this reason we are called Achaemenids". Achaemenes built the state Parsumash in the southwest of Iran and was succeeded by Teispes, who took the title "King of Anshan" after seizing Anshan city and enlarging his kingdom further to include Pars proper. Ancient documents mention that Teispes had a son called Cyrus I, who also succeeded his father as "king of Anshan". Cyrus I had a full brother whose name is recorded as Ariaramnes.

In 600 BC, Cyrus I was succeeded by his son, Cambyses I, who reigned until 559 BC. Cyrus the Great was a son of Cambyses I, who named his son after his father, Cyrus I. There are several inscriptions of Cyrus the Great and later kings that refer to Cambyses I as the "great king" and "king of Anshan". Among these are some passages in the Cyrus cylinder where Cyrus calls himself "son of Cambyses, great king, king of Anshan". Another inscription (from CM's) mentions Cambyses I as "mighty king" and "an Achaemenian", which according to the bulk of scholarly opinion was engraved under Darius and considered as a later forgery by Darius. However Cambyses II's maternal grandfather Pharnaspes is named by Herodotus as "an Achaemenian" too. Xenophon's account in Cyropædia further names Cambyses's wife as Mandane and mentions Cambyses as king of Iran (ancient Persia). These agree with Cyrus's own inscriptions, as Anshan and Parsa were different names of the same land. These also agree with other non-Iranian accounts, except at one point from Herodotus stating that Cambyses was not a king but a "Persian of good family". However, in some other passages, Herodotus's account is wrong also on the name of the son of Chishpish, which he mentions as Cambyses but, according to modern scholars, should be Cyrus I.

The traditional view based on archaeological research and the genealogy given in the Behistun Inscription and by Herodotus holds that Cyrus the Great was an Achaemenid. However it has been suggested by M. Waters that Cyrus is unrelated to the Achaemenids or Darius the Great and that his family was of Teispid and Anshanite origin instead of Achaemenid.

Early life

Cyrus was born to Cambyses I, King of Ansan and Mandane, daughter of Astyages, King of Media during the period of 600-599 BC or 576-575 BC. According to Herodotus, Astyages had two dreams in which a flood, and then a series of fruit bearing vines, emerged from her pelvis, and covered the entire kingdom. These were interpreted by his advisers as a foretelling that his grandson would one day rebel and supplant him as king. Astyages summoned his daughter Mandane, at the time pregnant with Cyrus, back to Ectabana to have the child killed. Harpagus delegated the task to Mithradates, one of the shepherds of Astyages, who raised the child and passed off his stillborn son to Harpagus as the dead infant Cyrus. Cyrus lived in secrecy, but when he reached the age of 10, during a childhood game, he had the son of a nobleman beaten when he refused to obey Cyrus's commands. As it was unheard of for the son of a shepherd to commit such an act, Astyages had the boy brought to his court, and interviewed him and his adopted father. Upon the shepherd's confession, Astyages sent Cyrus back to Persia to live with his biological parents. However, Astyages summoned the son of Harpagus, and in retribution, chopped him to pieces, roasted some portions while boiling others, and tricked his adviser into eating his child during a large banquet. Following the meal, Astyages' servants brought Harpagus the head, hands and feet of his son on platters, so he could realize his inadvertent cannibalism.

In another version, Cyrus was presented as the son of a poor family that worked in the Median court. These folk stories are, however, contradicted by Cyrus's own testimony, according to which he was preceded as king of Persia by his father, grandfather and great-grandfather. Upon his return, Cyrus married Cassandane who was an Achaemenian and the daughter of Pharnaspes who bore him two sons, Cambyses II and Bardiya along with three daughters, Atossa, Artystone, and Roxane. Cyrus and Cassandane were known to love each other very much - Cassandane said that she found it more bitter to leave Cyrus than to depart her life. After her death, Cyrus insisted on public mourning throughout the kingdom. The Nabondius Chronicle states that Babylonia mourned Cassandane for six days (identified from 21–26 March 538 BC). After his father's death, Cyrus inherited the Persian throne at Pasargadae which was a vassal of Astyages. It is also noted that Strabo has said that Cyrus was originally named Agradates by his stepparents; therefore, it is probable that, when reuniting with his original family, following the naming customs, Cyrus's father, Cambyses I, named him Cyrus after his grandfather, who was Cyrus I.

Median Empire

Though his father died in 551 BC, Cyrus the Great had already succeeded to the throne in 559 BC; however, Cyrus was not yet an independent ruler. Like his predecessors, Cyrus had to recognize Median overlordship. During Astyages's reign, the Median Empire may have ruled over the majority of the Ancient Near East, from the Lydian frontier in the west to the Parthians and Persians in the east.

According to the Nabonidus Chronicle, Astyages launched an attack against Cyrus, "king of Ansan." From Classical authors, it is known that Astyages placed Harpagus in command of the Median army to conquer Cyrus. However, Harpagus contacted Cyrus and encouraged his revolt against Media, before eventually defecting along with several of the nobility and a portion of the army. This mutiny is confirmed by the Nabonidus Chronicle. Babylonian texts suggest that the hostilities lasted for at least three years (553-550), and the final battle resulted in the capture of Ecbatana. According to Classical authors, Cyrus spared the life of Astyages and married his daughter, Amytis. This marriage pacified several vassal including the Bactrians, Parthians, and Saka.

With Astyages out of power, all of his vassals (including many of Cyrus's relatives) were now under his command. His uncle Arsames, who had been the king of the city-state of Parsa under the Medes, therefore would have had to give up his throne. However, this transfer of power within the family seems to have been smooth, and it is likely that Arsames was still the nominal governor of Parsa, under Cyrus's authority—more of a Prince or a Grand Duke than a King. His son, Hystaspes, who was also Cyrus's second cousin, was then made satrap of Parthia and Phrygia. Cyrus the Great thus united the twin Achamenid kingdoms of Parsa and Anshan into Persia proper. Arsames would live to see his grandson become Darius the Great, Shahanshah of Persia, after the deaths of both of Cyrus's sons. Cyrus's conquest of Media was merely the start of his wars.

Lydian Empire and Asia Minor

While in Sardis, Croesus sent out requests for his allies to send aid to Lydia. However, near the end of the winter, before the allies could unite, Cyrus the Great pushed the war into Lydian territory and besieged Croesus in his capital, Sardis. Shortly before the final Battle of Thymbra between the two rulers, Harpagus advised Cyrus the Great to place hisdromedaries in front of his warriors; the Lydian horses, not used to the dromedaries' smell, would be very afraid. The strategy worked; the Lydian cavalry was routed. Cyrus defeated and captured Croesus. Cyrus occupied the capital at Sardis, conquering the Lydian kingdom in 546 BC. According to Herodotus, Cyrus the Great spared Croesus's life and kept him as an advisor, but this account conflicts with some translations of the contemporary Nabonidus Chronicle (the King who was himself subdued by Cyrus the Great after conquest of Babylonia), which interpret that the king of Lydia was slain.

Before returning to the capital, a Lydian named Pactyas was entrusted by Cyrus the Great to send Croesus's treasury to Persia. However, soon after Cyrus's departure, Pactyas hired mercenaries and caused an uprising in Sardis, revolting against the Persian satrap of Lydia, Tabalus. With recommendations from Croesus that he should turn the minds of the Lydian people to luxury, Cyrus sent Mazares, one of his commanders, to subdue the insurrection but demanded that Pactyas be returned alive. Upon Mazares's arrival, Pactyas fled to Ionia, where he had hired more mercenaries. Mazares marched his troops into the Greek country and subdued the cities of Magnesia and Priene. The end of Pactyas is unknown, but after capture, he was probably sent to Cyrus and put to death after a succession of tortures.

Mazares continued the conquest of Asia Minor but died of unknown causes during his campaign in Ionia. Cyrus sent Harpagus to complete Mazares's conquest of Asia Minor. Harpagus captured Lycia, Cilicia and Phoenicia, using the technique of building earthworks to breach the walls of besieged cities, a method unknown to the Greeks. He ended his conquest of the area in 542 BC and returned to Persia.

Neo-Babylonian Empire

By the year 540 BC, Cyrus captured Elam (Susiana) and its capital, Susa. The Nabonidus Chronicle records that, prior to the battle(s), Nabonidus had ordered cult statues from outlying Babylonian cities to be brought into the capital, suggesting that the conflict had begun possibly in the winter of 540 BC. Near the beginning of October, Cyrus fought the Battle of Opis in or near the strategic riverside city of Opis on the Tigris, north of Babylon. The Babylonian army was routed, and on October 10, Sippar was seized without a battle, with little to no resistance from the populace. It is probable that Cyrus engaged in negotiations with the Babylonian generals to obtain a compromise on their part and therefore avoid an armed confrontation. Nabonidus was staying in the city at the time and soon fled to the capital, Babylon, which he had not visited in years.

Two days later, on October 7 (proleptic Gregorian calendar), Gubaru's troops entered Babylon, again without any resistance from the Babylonian armies, and detained Nabonidus. Herodotus explains that to accomplish this feat, the Persians, using a basin dug earlier by the Babylonian queen Nitokris to protect Babylon against Median attacks, diverted the Euphrates river into a canal so that the water level dropped "to the height of the middle of a man's thigh", which allowed the invading forces to march directly through the river bed to enter at night. On October 29, Cyrus himself entered the city of Babylon and detained Nabonidus.

Prior to Cyrus's invasion of Babylon, the Neo-Babylonian Empire had conquered many kingdoms. In addition to Babylonia itself, Cyrus probably incorporated its subnational entities into his Empire, including Syria, Judea, and Arabia Petraea, although there is no direct evidence of this fact.

After taking Babylon, Cyrus the Great proclaimed himself "king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four corners of the world" in the famous Cyrus cylinder, an inscription deposited in the foundations of the Esagila temple dedicated to the chief Babylonian god, Marduk. The text of the cylinder denounces Nabonidus as impious and portrays the victorious Cyrus pleasing the god Marduk. It describes how Cyrus had improved the lives of the citizens of Babylonia, repatriated displaced peoples and restored temples and cult sanctuaries. Although some have asserted that the cylinder represents a form of human rights charter, historians generally portray it in the context of a long-standing Mesopotamian tradition of new rulers beginning their reigns with declarations of reforms.

Cyrus the Great's dominions comprised the largest empire the world had ever seen. At the end of Cyrus's rule, the Achaemenid Empire stretched from Asia Minor in the west to the northwestern areas of India in the east.

Death

The details of Cyrus's death vary by account. The account of Herodotus from his Histories provides the second-longest detail, in which Cyrus met his fate in a fierce battle with the Massagetae, a tribe from the southern deserts of Khwarezmand Kyzyl Kum in the southernmost portion of the steppe regions of modern-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, following the advice of Croesus to attack them in their own territory. The Massagetae were related to the Scythians in their dress and mode of living; they fought on horseback and on foot. In order to acquire her realm, Cyrus first sent an offer of marriage to their ruler, Tomyris, a proposal she rejected.

He then commenced his attempt to take Massagetae territory by force (ca. 529), beginning by building bridges and towered war boats along his side of the river Jaxartes, or Syr Darya, which separated them. Sending him a warning to cease his encroachment in which she stated she expected he would disregard anyway, Tomyris challenged him to meet her forces in honorable warfare, inviting him to a location in her country a day's march from the river, where their two armies would formally engage each other. He accepted her offer, but, learning that the Massagetae were unfamiliar with wine and its intoxicating effects, he set up and then left camp with plenty of it behind, taking his best soldiers with him and leaving the least capable ones. The general of Tomyris's army, Spargapises, who was also her son, and a third of the Massagetian troops, killed the group Cyrus had left there and, finding the camp well stocked with food and the wine, unwittingly drank themselves into inebriation, diminishing their capability to defend themselves when they were then overtaken by a surprise attack. They were successfully defeated, and, although he was taken prisoner, Spargapises committed suicide once he regained sobriety. Upon learning of what had transpired, Tomyris denounced Cyrus's tactics as underhanded and swore vengeance, leading a second wave of troops into battle herself. Cyrus the Great was ultimately killed, and his forces suffered massive casualties in what Herodotus referred to as the fiercest battle of his career and the ancient world. When it was over, Tomyris ordered the body of Cyrus brought to her, then decapitated him and dipped his head in a vessel of blood in a symbolic gesture of revenge for his bloodlust and the death of her son. However, some scholars question this version, mostly because Herodotus admits this event was one of many versions of Cyrus's death that he heard from a supposedly reliable source who told him no one was there to see the aftermath.

Herodotus also recounts that Cyrus saw in his sleep the oldest son of Hystaspes (Darius I) with wings upon his shoulders, shadowing with the one wing Asia, and with the other wing Europe. Iranologist, Ilya Gershevitch explains this statement by Herodotus and its connection with the four winged bas-relief figure of Cyrus the Great in the following way:

Herodotus, therefore as I surmise, may have known of the close connection, between this type of winged figure, and the image of the Iranian majesty, which he associated with a dream prognosticating, the king's death, before his last, fatal campaign across the Oxus.

Dandamayev says maybe Persians took back Cyrus' body from the Massagetae, unlike what Herodotus claimed.

Ctesias, in his Persica, has the longest account, which says Cyrus met his death while putting down resistance from theDerbices infantry, aided by other Scythian archers and cavalry, plus Indians and their elephants. According to him, this event took place northeast of the headwaters of the Syr Darya. An alternative account from Xenophon's Cyropaediacontradicts the others, claiming that Cyrus died peaceably at his capital. The final version of Cyrus's death comes fromBerossus, who only reports that Cyrus met his death while warring against the Dahae archers northwest of the headwaters of the Syr Darya.