With television reruns of The Great Escape almost as unavoidable as Brussels sprouts at Christmas, Steve McQueen’s doomed motorbike leap is a movie moment burned into popular imagination on both sides of the Atlantic. The scene in the 1963 film, apparently included at McQueen’s request, is one of the larger departures from a truthful back story that needed no embellishment to be one of the most fascinating and tragic tales from an era that lacked neither.

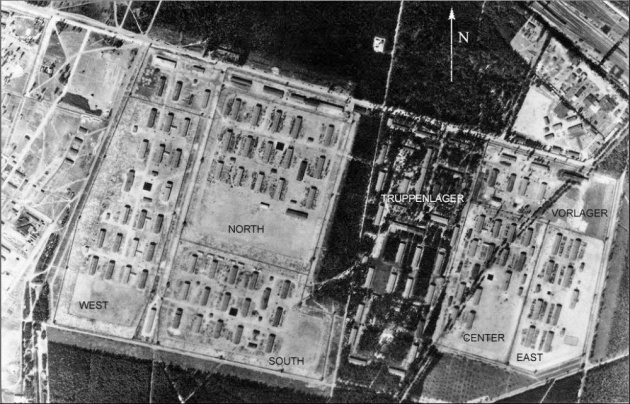

Stalag Luft III was a real prisoner of war camp in World War II, run by the German air force, the Luftwaffe, in Lower Silesia. Frustrated by escape ff ff attempts by Allied airmen, the Germans had deliberately built it on soft sand it was supposed to be tunnel proof. On a freezing, moonless March night in 1944, it was the scene of a mass escape by Allied POWs. More than a year in the planning and execution stages, its scale was unprecedented, even for a scheme hatched by RAF officers, who were duty bound to try and escape.

Under the leadership of ‘Big X’, Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, some 600 men excavated three secret tunnels – famously known as Tom, Dick and Harry – using cutlery and metal cans as tools, dispersing the displaced sand in various ingenious ways. The tunnels, which ran up to 30-feet deep through soft sand, were supported by a wooden framework made from pieces of the prisoners’ beds. Air was pumped into the warrens and electric lights were rigged up. A sophisticated Escape Committee directed operations, which included the procurement of German money and the forging of documents to aid the escapees once they’d sprung.

One of the tunnels was filled in and another discovered by the Germans before a breakout date was set. Not everyone involved could possibly get out, but 100 men were shortlisted, those deemed to have the best chance of success, with a further 100 lined up to follow if possible.

At 10.30pm on Friday 24 March 1944, men began crawling along the last remaining tunnel, Harry, only to find the door frozen shut. When it was finally opened, the exit proved to be several feet short of the woods and there was snow on the ground, so footprints would be seen.

Instead of the planned one-man-a-minute approach, the escape rate was slowed to ten per hour to avoid detection by the sentries, with 76 POWs getting away before the alarm was raised. Most were quickly recaptured or killed, but three managed to make home runs. Unlike the film, which portrays an Australian, an Englishman and an American making it out alive, the successful runaways were Dutch and Norwegian. Their stories are extraordinary.

THE FLEEING DUTCHMAN:

The 18th man to emerge from the tunnel was Flight Lieutenant Bram van der Stok, a Dutch pilot. Van der Stok flew with Holland’s Luchtvaartbrigade until the surrender to Germany in 1940, whereupon he escaped to Britain as a stowaway on a Swiss ship. Joining the RAF, he became a Flying Ace, with six confirmed kills during aerial battles with the Luftwaffe, until being shot down and captured on a mission over France in 1942.

Van der Stok was fluent in German and familiar with the terrain he would need to traverse. The Escape Committee considered him a strong contender to make a home run he was assigned a top 20 position.

To stay nimble, van der Stok opted to travel alone. He had an early scare, however, when he ran straight into a German civilian in the woods beyond the prison, who questioned why he was wandering around in the dark. Well prepared for various scenarios, he claimed to be a Dutch labourer who’d become disorientated and lost during the air raid that was taking place. Convinced, the good citizen even led the runaway to the railway station.

Unfortunately, the heavy bombing raid conducted by his RAF buddies on Berlin that night resulted in severe delays to the train service to Breslau (now Wrocław). During an anxious three hour wait, a number of other escapees appeared at the station, all dressed in prison made disguises to appear as labourers and civilians. The POWs avoided all eye contact, and willed the time away as fast as possible.

Also on the platform was a German woman who worked at Stalag Luft III as a censor. She became suspicious of one of the men Thomas Kirby Green, a British pilot and advised military police to question him. Flight Lieutenant Gilbert William Walenn, the prison forger, had done an excellent job, however,and Kirby Green’s papers passed the inspection. At 3.30am the train finally arrived and van der Stok boarded. On the train were eight other jail breakers, including Bushell and his escape partner Bernard Scheidhauer, who’d been numbers two and three out of the tunnel.

At 4.55am, back at Stalag Luft III, a German guard spotted the 77th man as he emerged from the tunnel and the alarm was raised. Five minutes later, the train carrying van der Stok rolled into Breslau. Word of the escape had not travelled that far yet and the station was free of Gestapo. The Dutchman took a train to Dresden, where he hid in a cinema and slept before catching another train to the border with the Netherlands at Bentheim. On this leg, his papers were demanded and inspected four times. The escape must have been discovered, he assumed correctly.

The Nazi machine was going into overdrive to find the escapees, but the forged paperwork held up and he passed into the German occupied Netherlands, travelling through Oldenzaal to Utrecht, where his family lived. Rather than risk capture by visiting them, he stayed with a friend.

Assisted by Belgian resistance, van der Stok then cycled into Belgium. There he picked up another new identity and story, staying with a Dutch family in Brussels. He moved via Paris to Toulouse, and then to Saint-Gaudens, where he was united with the Maquis (guerillas of the French Resistance). With fellow fugitives and a mountain guide, he made a harrowing journey in freezing conditions across the Pyrenees to Lérida in Spain.

Although sympathetic to the Axis powers throughout World War II, Franco’s Spain was officially neutral and actively frustrated Germany’s attempts to seize control of Gibraltar, which is where van der Stok found sanctuary on 8 July. From here he was flown to Bristol in a Douglas Dakota transport, arriving in England three-and-a-half months after his escape. He later rejoined his RAF squadron and took part in D-Day and operations to counter Germany’s V-1 flying bomb attacks on south-east England.

SCANDINAVIAN SPRING:

Sergeant Per Bergsland and Lieutenant Jens Müller were Norwegian pilots who had escaped their country after the German occupation in 1940 and travelled to Britain, where they joined the RAF. Both survived being shot down in separate missions over occupied Europe, and both wound up incarcerated in Stalag Luft III.

They spoke excellent German and their chances at staging a successful home run were rated highly by the Escape Committee, so they emerged from the tunnel as numbers 43 and 44. Safely arriving at the railway station, they boarded the 2.04am train to Frankfurt, posing as Norwegian electricians and carrying papers saying they had been transferred from one labour camp to a place in Stettin.

At 6am they arrived in Frankfurt and two hours later hopped on a train to Küstrin. While having a beer in the station, they were approached by a military policeman who inspected their papers and believed their story. Catching a train to Stettin, they had another beer and hid out in the cinema to wait for nightfall, whereupon they visited a French Brothel at 17 Klein Oder Strasse, which the Escape Committee had identified as a good place to find help. There they met a Swedish sailor who directed them into the docks, promising to get them onto his ship – it left without them, however. They laid low the following day, returning to the brothel in darkness. Again, an offer of help came, this time from two Swedish sailors who successfully smuggled them aboard their ship. It wasn’t due to leave until morning, however, and the sailors knew the Germans would search it first, so the pair hid overnight in the anchor locker. The search failed to unearth the stowaways, and the Norwegians were free. Docking in Gothenburg, the men reported to the British consulate. From here they travelled by train to Stockholm and flew from Bromma airport to Scotland in two tiny Mosquito aeroplanes, arriving in London on 8 April 1944.

THE 50:

Hitler wanted all of the recaptured POWs shot, alongside the camp commandant and the guards who were on duty during the breakout. He was dissuaded from this, but did order the execution of 50 runaways, including Bushell, Scheidhauer and Walenn, which constituted a war crime under the Geneva Convention. The remaining 23 prisoners were sent back to prison camps – 17 to Stalag Luft III, four to Sachsenhausen and two to Colditz Castle.

The Untold Story of The Great Escape

Posted on at