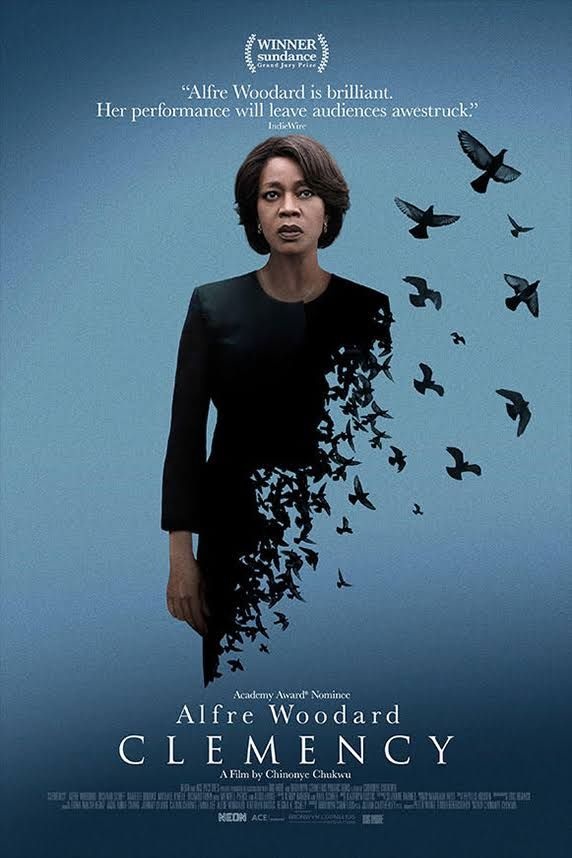

Pictured: Prison warden Bernadine Williams (Alfre Woodard) oversees the execution of an inmate in the prison drama, Clemency, written and directed by Chinonye Chukwu. Still courtesy of Sundance Institute / NEON

Contains spoilers

Who’d be a prison warden? The inmates don’t like you – they have their own issues to deal with. The staff resent you – you earn so much more than they do. The media demonises you – you represent the institution that sends prisoners to their graves. Families of the inmates are sickened by you – why can’t you help their incarcerated loved ones? Lawyers are antagonised by you - because you won’t assist their clients. One person is grateful to you – the local bar owner. You represent some good business. What – you can’t sleep? Paid-for programmers love you.

Bernadine Williams (Alfre Woodard), the protagonist of writer-director Chinonye Chukwu’s prison-based drama, Clemency, is one such warden. Hard as stone, she gives the media nothing. Outside her window, protestors shout the name of one of her guests, Anthony Woods (Aldis Hodge), who has been given the death sentence for the killing of a police officer. He was at the scene but did not discharge the murder weapon. He’s been on Death Row for fifteen years, aided by a compassionate lawyer (Richard Schiff) who is on the verge of retiring. ‘You gave me hope,’ Anthony insists, having apologised for sending the lawyer away after hearing about the passing of his mother. Naturally, Anthony wasn’t given leave to attend the funeral. The lawyer is heartbroken that all his efforts appear to be in vain, hinging on the clemency of the State Governor.

Bernadine is a functionary. She has the thankless task of being in the room when inmates are put to death by lethal injection. It is a cocktail of drugs, the last of which stops heart function. In the opening sequence, a Latino gentleman is strapped in for his death dose. Only the medic cannot find a vein. He tries the arm – no good. The foot – are you kidding? Finally, his stomach. The prisoner is in agony. The curtains are closed on spectators. The priest barely knows where to look. The prisoner bleeds through his belly. The intubation is dislodged. The prisoner is alive, in unspeakable agony. What to do? The emotion that hangs over the room is embarrassment. How could they mess it up? Why was the prisoner not fed water? It is a relief when the prisoner dies. However, there are questions to be answered.

This isn’t Bernadine’s only thankless task. She fends off the media and a contingent of lawyers who want to see Anthony. If they aren’t on the visitors’ list, they aren’t coming in. You might expect that Bernadine would answer to the late Latino’s mother, explaining what happened. There is no such meeting. We see Bernadine offer the woman hope. There could be call from the Governor. No such exercise of heart. Bernadine isn’t the type of warden who lobbies the Governor’s office or pretends to know their mind. She remains in her office, fighting fires. She is the one who has to offer prisoners the choice of a final meal, within reason. She completes a form with a heavy heart, ticking the box ‘no meal/fasting’.

Pictured: Warden Bernadine (Alfre Woodard) in a scene from the film Clemency, written and directed by Chinonye Chukwu. Still courtesty of NEON

Pictured: Warden Bernadine (Alfre Woodard) in a scene from the film Clemency, written and directed by Chinonye Chukwu. Still courtesty of NEON

At certain points during the film, Chukwu’s camera rests of Bernadine’s silent face. In her first scene, she doesn’t respond when addressed formally. ‘Warden?’ No acknowledgement. ‘Warden?’ Still, nothing. ‘Bernadine? She tilts her head towards the speaker. It is as if only the mention of her name reminds her of her humanity.

Bernadine’s husband (Wendell Pierce) is there for the nightmares, her lurch forward into heavy panting as if almost drowning in her sleep. She retreats to the lounge and watches TV. ‘I’d like to sleep with my wife,’ Mr Williams explains. ‘Is it too much to ask?’

After work, Bernadine goes for a drink and when a junior colleague joins her, allows alcohol to take her senses. She intends to drive home drunk, but the colleague won’t let her. She begins the evening by raising a work matter. The colleague bats it away. ‘How’s the children – you have two, don’t you?’ Bernadine asks to demonstrate her interest in other stuff. ‘You really suck at small talk,’ the colleague responds.

In a strange manner, Bernadine is as confined as the prisoners in her care, only her entrapment is self-enforced. On the evening of her wedding anniversary, plying her with white wine and a favourite song, her husband tries to persuade her to retire. Bernadine is appalled. He then tries to leave her, stating an intention to check into a hotel. She visits him at his place of work (a school), something he doesn’t reciprocate. (Can you blame him?) Finally, he concludes, ‘this is our home’.

There is an unexpected development. Anthony receives a letter with a picture of his son, now almost fifteen. His ex-girlfriend, the one who didn’t stand by him at his trial, who decided during pregnancy not to burden an unborn child with the matter of the father’s incarceration, she gives Anthony the big speech that she isn’t sorry. Anthony is desperate to see his son – to have a family. This hope is firmly dashed.

Hodge is striking in two sequences. Firstly, when he exercises alone, pounding a basketball against the hard ground as he paces around an exercise square – the camera reveals that wire mesh acts as a ceiling. He doesn’t have anywhere to shoot the basketball. Secondly, when Anthony is at his most despondent, he looks at the hand-drawn pictures on the wall of birds of flight and slams his forehead bloodily against the wall. ‘I will decide when I die!’ he cries as he is restrained by two officers.

In the latter half of the film, you wonder where the conflict is. Does Bernadine think she is fulfilling a public duty? Can she only function when she keeps her emotional distance? At one point, as Anthony expects a visit, she pours him a glass of water. Anthony is grateful. Anticipation quickly moves to disappointment. The priest, there to console Anthony, is surplus to requirements. The film builds to an extended close-up on Bernardine’s face, having heard Anthony protest his innocence one last time and express to the family of the deceased police officer, his sorrow for their loss. Anthony has been told, not least by his ex-girlfriend, that, unlike her, he is loved. ‘All we want is to be noticed,’ someone says at some point. Bernadine for the most part wants to be invisible.

The final scene is about the lowering of Bernadine’s professionalism, her reconnection with her humanity. It feels beside the point. Surely, she should feel something for a broken justice system if Anthony is, as he attests, innocent. Bernadine should not want to be a part of the execution of those whose defence lawyers were unpersuasive or who had juries that were too prejudiced. It isn’t about her. We should be thinking about Anthony and how he was judged too quickly. We should feel that in Death Row cases, the burden of proof should be higher.

I found myself distracted rather than moved by that final close-up, that fixation on the water running below Bernadine’s nostrils. I found her unresponsiveness contrived. In dramas, you take for granted that directors will make the right choice to elicit a reaction. Here, the ending only seemed to work for part of the audiences - those who felt compelling to clap during an end-credits song that also felt misjudged.