The battle plan that Nelson had formulated for Trafalgar was a simple one – but it came at the end of a long and complicated campaign.

In May 1803, the brief Peace of Amiens between Britain and France had ended and the two nations were once again at war. Napoleon, who had been crowned Emperor of the French in December 1804, decided to invade England and assembled a large army on the French coast around Boulogne. His plan was to ferry his troops across the English Channel on barges. But before he could attempt such an expedition, he had to gain control of the Channel.

In March 1805, a French fleet under the command of Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve sailed out of Toulon and, after linking up with ships from France’s new ally, Spain, made for the West Indies. The plan was to rendezvous with more French ships, creating a fleet large enough to dominate the Channel. Admiral Horatio Nelson, though, was determined to prevent this from happening.

Having searched for Villeneuve’s fleet in the Mediterranean, Nelson gave chase and, by early June, he too was in the Caribbean. The harassed Villeneuve re-crossed the Atlantic but, with Nelson having warned the Admiralty of the French fleet’s movements, he was intercepted on Cape Finisterre by an English fleet under Sir Robert Calder. He was forced to turn south and, in September, took refuge in Cádiz.

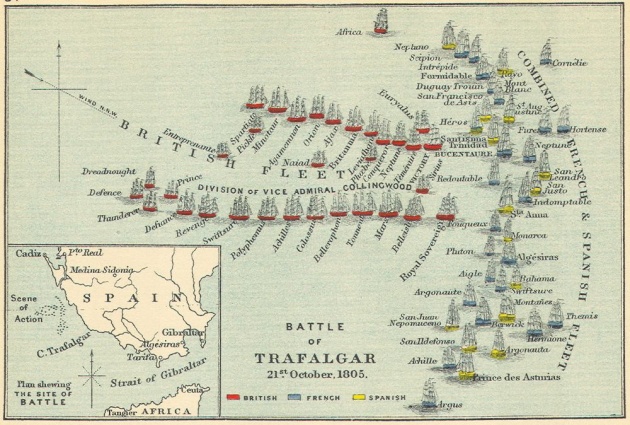

BATTLE STATIONS:

With no fleet to protect his invasion force, Napoleon abandoned his plans to invade Britain and instead moved east to deal with the armies of Britain’s allies, Austria and Russia.

Villeneuve, though, was left bottled up in Cádiz, blockaded by a British fleet commanded by Nelson. Three weeks into October, under pressure from Napoleon, Villeneuve finally attempted to break out and sail into the Mediterranean.

Nelson was waiting for him. The well-drilled British crews ‘cleared for action’, removing anything that might get in the way during the ensuing battle, dousing flammable materials with water and scattering sand on the decks to prevent the men from slipping. Meanwhile, down below, the ships’ surgeons were preparing temporary hospitals and laying out the grim tools of their trade.

Once in sight of the enemy, the drummers of the Royal Marines ‘beat to quarters’ – the signal for the crews to take up their action stations. As the British ships closed in on their enemies, Nelson ordered a signal to be displayed aboard his flagship HMS Victory: “England expects that every man will do his duty.” Admiral Collingwood, Nelson’s second-in-command, was not impressed. “I do wish Nelson would stop signalling,” he muttered. “We all know well enough what to do.”

In fact, Collingwood’s acerbic comment contained an important truth: Nelson’s captains did indeed know what to do. While o the coast of Spain, Nelson had invited them to dinner on board Victory and personally explained his plan for the approaching battle.

Traditional naval tactics would have seen the two fleets deployed in two long parallel lines but, instead, Nelson planned to attack in two columns. One, led by Collingwood, would attack the rear of the enemy line of battle while the other, led by Nelson, would tackle the centre. By breaking the allied line of battle in this way, Nelson would bring about a series of ship-toship actions in which the superior British seamanship and gunnery would prove decisive. It would also force ships in the vanguard of the enemy fleet to turn back to support the ships at the rear, which would take a long time. Finally, he gave his captains freedom of action by telling them: “No captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of the enemy.”

Such a head-on attack would inevitably expose his ships to a torrent of gunnery with no opportunity to reply. To minimise the damage sustained, Nelson aimed to close with the enemy as quickly as possible. He ordered his ships to carry their full complement of sails, and put his largest battleships at the front of his columns. Collingwood’s ship, the Royal Sovereign, was the first into action. It broke the Franco-Spanish line at about noon and fought alone for 20 minutes before the rest of the fleet could join it. Collingwood paced the deck of his ship, ignoring pleas to remove his conspicuous cocked hat. “Let me alone,” he replied. “I have always fought in a cocked hat, and always shall.” He carried on pacing, calmly eating an apple.

As Victory approached the enemy line at the head of the second column, she took a heavy battering. Her ship’s wheel was shot away, but still she kept on coming. As she sailed past the stern of Villeneuve’s flagship Bucentaure, Victory’s well-trained gunners were at last able to fire, unleashing a devastating broadside. Shot smashed through the French ship, disabling 20 of her guns, killing and wounding 200 of her men and effectively putting her out of action.

As more and more British ships came into action, French and Spanish casualties began to mount. Captain Servaux of the French ship Fougueux described the eects of one of the Royal Sovereign’s broadsides: “Most of the sails and rigging were cut to pieces, while the upper deck was swept clear of the greater number of the seamen working there, and of the soldier sharpshooters.”

Sailors suered horrific wounds. Men were disembowelled or had limbs or heads shot of – a single French cannonball killed eight marines on the poop deck of HMS Victory. Balls smashed into decks and bulwarks, tearing o jagged splinters of wood that caused terrible injuries to anyone they hit. Men were crushed by falling spars and masts or loose cannon. Those on the gundecks were deafened by the noise and blinded by the smoke from their guns but were better o than men on the exposed upper decks.

After dealing with the Bucentaure, Nelson’s flagship found itself locked in combat with another French ship, the Redoutable. While Victory’s gunners blazed away below decks, sharpshooters up in the masts of the Redoutable opened a withering fire upon the British ship’s exposed quarterdeck. Thomas Hardy, Victory’s captain, gave the order to take cover but Nelson continued to pace the deck in his distinctive admiral’s uniform – and soon the inevitable happened: he was struck in the shoulder by a musket ball that passed through a lung and hit his spine.

Nelson was carried down to the orlop deck in agony and died at about 4.30pm – but not before he’d heard the news that the battle had been won. Seventeen enemy ships had been captured and one had blown up.

No sooner had the battle ended than a savage storm blew up, and the British struggled in heavy seas to save their own damaged ships as well as the ships they’d captured. In the end, they saved all of their own ships and four of their prizes; the rest sank or were wrecked, or were destroyed by the British to prevent recapture by the French.

Two days after the battle, five surviving allied ships made a daring sortie from Cádiz and managed to recapture two ships. However, one of these was subsequently wrecked, along with three of the rescuers. Finally, on 4 November, four fugitive allied ships were intercepted and captured in the Bay of Biscay. When the final ripples of the battle had died away, the allies had lost no fewer than 24 ships out of their combined fleet of 33. No British ships had been lost.

Trafalgar (Nelson's Last Victory)

Posted on at