It was the Byzantine Empire, which was to realize Alexander's idea- Macedonian Panhellenism- in face of an Asia in revolt, and realized it for the Greeks.

-Rene Grousset-

The Roman Empire began to break up in the 4th century. At this same time, the Christian religion was growing in strength. By A.D. 313 the Roman Emperor Constantine had made Christianity the official religion. He moved his capital from Rome to the old Greek city of Byzantium. There he built a new city which he named Constantinople (now Istanbul).

When the Roman Empire was divided into two parts, Eastern and Western, Constantinople was the capital of the East, and Rome became the capital of the west. The art of both western and Eastern regions was basically Christian. But historians generally describe that of the West as early Christian art and that of the East as Byzantine art.

The purpose of early Christian and Byzantine art was to glorify the Christian religion and spread its teachings. The Church paid artists to express the meaning and aims of Christianity in their work.

GEOGRAPHY AND DEMOGRAPHY

The Roman Empire was one of the largest in history, with contagious territories throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. The Latin phrase imperium sine fine (empire without end) express the ideology that neither time and space limited the Empire. In Virgil's epic poem the Aeneid, limitless empires is said to be granted to the Romans by their supreme deity Jupiter. This claim of the universal dominion was renewed and perpetuated when the Empire came under Christian rule in the 4th century.

In reality, Roman expansion was mostly accomplished under the republic, though parts of the Northern Europe were conquered in the 1st century AD when Roman control in Europe, Africa, and Asia was strengthened. During the reign of Augustus, a " global map of the known world" was displayed for the first time in the public at Rome, coinciding with the composition of the most comprehensive work on political geography that survives from antiquity, the Geography of Pontic Greek writer Strabo. When Augustus died, the commemorative account of his achievements (Res Gestae) prominently featured the geographical cataloging of people and places within Empire. Geography, the census, and the meticulous keeping of written records were a central concern of the Roman Imperial administration.

The Empire reached its largest expanse under Trajan ( reigned 98-117), encompassing an area of 5 million square kilometers. The traditional population estimate of 55-60 million inhabitants accounted for one sixth and one-fourth of the world's total population and made it the largest population of any unified political entity in the West until the mid-19th century. Recent demographic studies have argued for a population peak ranging from 70 million to more than 100 million. Each of the three largest cities in the Empire-Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch- was almost twice the size of any European city at the beginning of the 17th century.

As the historian Christopher Kelly has described it:

Then the Empire stretched from Hadrian's Wall in drizzle-soaked northern England to the sun-baked banks of the Euphrates in Syria; from the great Rhine-Danube river system, which

snaked across the fertile, flat lands of Europe from the Low Countries to the Black Sea, to the

rich plains of the north African east and the luxuriant gash of the Nile Valley in Egypt. The

empire completely circled the MEditerranean...referred to by its conquerors as mare nostrum-'our sea'.

Trajan's successors Hadrian adopted a policy of maintaining rather than expanding the empire. Borders (fines) were marked, and the frontiers (limited) patrolled. The most heavily fortified borders were the most unstable. Hadrian's Wall, which separated the Roman world from what was perceived as an ever present barbarian threat, is the primary surviving monument of this effort.

-Read more: Wikipedia

EARLY CHRISTIAN CHURCHES

The Western Empire was invaded many times by Germanic and Asiatic tribes. As the invaders became more civilized, they accepted Christianity along with Roman culture. The earliest Christians had worshipped secretly in their homes and in the catacombs (burial chambers) under the cities. After Christianity was made the official state religion, pagan (non-Christian) temples, tombs, and other buildings were taken over for the worship. These buildings later influenced the design of new churches.

There were two types of new churches, the basilican, and the central-plan type. (Image Courtesy: pixabay.com)

Banks into Churches

A basilica was a Roman building that had been used as a bank and the hall of justice. Many of these were turned into churches. A basilica was rectangular. It was usually twice as long it was wide and had a sloping roof. Two of four rows of columns divided the inside of the building into three or five aisles (passages).

When the building was used for Christian worship, men sat on one side of the central aisle and women on the other. At one end, there was a raised platform called apse, shaped like a half circle, where the Roman judge had sat. The altar was placed in this apse.

Constantine ordered two basilican churches to be built over the tombs of the Apostles Peter and Paul, in Rome. St Peter's, built in A.D 330, was destroyed in the early 1500s to make room for the present St Peter's. St Paul Outside the Walls, built between 324 and 386, was burned down in 1823 but was rebuilt on the original plans. It has a central nave and four side aisles.

Tombs into Churches

The central-plan church was either circular, octagonal (eight-sied) or in the form of a cross with arms of equal length. The roof was a dome (rounded). Such churches developed from the old circular or polygonal (many-sided) Roman temples and tombs. At first, these were used as Christian tombs. Later, they became places of worship. But because of their shape and size, they were not suitable for large crowds or processions. As a result, they were often just used for small services and baptisms when only a few people came together. Churches used for baptisms had a poor or font (basin) built in the center.

BYZANTINE ART

In the Byzantine world, some of the very early churches were basilicas, like those in Rome. The Roman builders had plenty of fine building material such as wood, marble, and stones. But in the Byzantine Empire, wood was scarce and there was no cheap source of marble. So buildings had to be built of concrete, brick or stone.

Byzantine architects did not invent the plans of building methods they used but copied them from the architecture of the Near East and Rome. They improved on the Roman dome because they found out how to place a round dome on the square base of the supporting walls. They did this by building up the stonework or brickwork into a triangle at the top of each of the four corners of the walls. This kind of building work is called a pendentive. The pendentives strengthened the walls and joined them to the dome.

Byzantine art: the richly decorated gold mosaic (Image Courtesy: pixabay.com

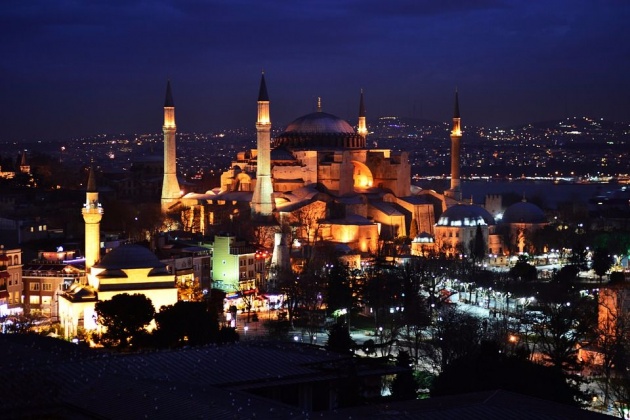

Hagia Sophia in Istanbul stands on the site of an ancient Greek temple. The interior is beautifully decorated with marble glass and mosaics. ( Image Courtesy: pixabay.com)

The St Mark's Church in Venice was built in the Byzantine style in the 11th century. Its domes are characteristic of the architecture of the East. ( Image Courtesy: pixabay.com)

Mosaics were often used in early Christian and Byzantine churches to illustrate religious stories. (Image Courtesy: pixabay.com)

The Finest Byzantine Building

The most famous and the most beautiful building in Byzantine world is the church of Hagia Sophia, in Constantinople. Hagia Sophia means 'holy wisdom', and the church was built to honor the Virgin Mary. It stands on the site of an ancient temple to Pallas Athene, the Greek goddess of wisdom.

The church was designed by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus. The building was begun in 532, and it is said that the emperor Justinian himself took charge of the work.

The pendentive of Hagia Sophia rests on four piers, or pillars. which have the lead instead of mortar between the stones. The great central dome is 107 feet (32.6 meters) across and 180 feet (55 meters) high. To make it lighter, the dome was made of a special light brick brought from the island of Rhodes. The builders supported the dome on two sides with half-domes and on the other two sides with arches, to make sure that it would not fall down.

There is a feeling of endless space in Hagia Sophia. When you stand inside the great church, you must look at one part at a time. Your eyes go from the pillars to the vaults (arched roofs), then to the smaller domes and finally to the huge central dome. From there a huge figure of Christ looks down.

The splendor of Hagia Sophia also comes from its color. The columns, taken from every corner of the Empire are of stone and marble of many different colors, including blue, green, and blood red. The floor is covered with marble mosaics (small pieces of glass or stone set in cement or plaster), and the walls shine with glass mosaics.

Byzantine Art Spreads to the West

Byzantine art flourished from the founding of Constantinople in 330 until it fell to the Turks in 1453. Many people in Europe soon began to copy Byzantine buildings. The Russians used many different kinds of domes on their churches. In 1063 the rich citizens of Venice hired Eastern artists to build the famous St Mark's Church which has five domes and gold mosaics. The Duke of Venice ordered all Venetians who traveled in, or traded with, the East to bring back precious materials. There were used to decorate the inside of this magnificent church.

The earliest Byzantine architecture, though determined by the longitudinal Basilica church plan developed in Italy. Favored the extensive use of large domes and vaults. Circular domes, however, were not structurally or visually suited to a longitudinal arrangement of the walls that supported them: thus, by the 10th century, a radial plan, consisting of four equal vaulted arms proceeding from a dome over their crossing, had been adopted in most areas. This central, radial plant was well suited to the hierarchical view of the universe emphasized by an Eastern Church. This view was made explicit in the iconographic scheme of the church decoration, set forth in the frescoes, or more often, mosaics, that covered the interiors of domes, walls, and of churches in a complete fusion of architectural and pictorial expression. In the top of the central dome was the severe figure of the Pantocrator (all-ruling Father). Below him, usually around the base of the dome were angels and archangels are and, on the walls, figures of the saints. The Virgin Mary was often pictured high in a half dome covering one of the four radial arms. The lowest real was that of the congregation. The whole church thus formed a microcosm of the universe. The iconographic scheme also reflected lithargy; narrative scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin, instead of being placed in chronological order along the walls, as in Western churches, were chosen for their significance as feast days and ranged around the church according to their theological significance.

-Britannica-

PAINTINGS AND MOSAICS

Soon after Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire, its leaders began to hire artists to decorate the walls and ceilings of the catacombs where they worshipped in secret. A few of those early wall paintings still survive in the dark tunnels.

Early Christians and Byzantine artists continued to use the mosaic method that they had learned from the Greeks and Romans. In early Christian mosaics, human figures in rich colors were sometimes set against a background of shimmering gold. The gold was used to show that those were spiritual subjects, quite apart from the everyday world.

Mosaic pictures cannot copy nature exactly as a painting. The early-Christian mosaics were very decorative. However, they had no perspective (depth) and appeared very flat. The human figures were very stiff and not as life like ass those in early Greek and Roman mosaics.

The mosaic of the Byzantine artists was often even less lifelike and are decorative than those of the early Christians. The Byzantine Empire was greatly influenced by the art of the Near East. Instead of copying nature, Eastern artists turned natural forms into flat patterns. So they would change the shape of the human body to make it fit in with their designs. Eastern artists were also fond of glowing color. Byzantine artists combined the art of the Near East with the classical art of the West.

In the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, there is a well-known mosaic picture of Justinian, an Emperor of the Byzantine Empire, with his attendants. It was made about 547. His stiff pose and magnificent robes make him look every inch of an Emperor. On the opposite wall is a good picture of his wife, the Empress Theodora, with her ladies-in-waiting. In the dome at the end of the church, Christ is shown among the angles.

In these two mosaics, the figures are stiff and the feet point downwards, suggesting that the bodies are floating. But the stiff, long bodies are not simply the result of using mosaic. Such figures belonged to the new Byzantine style in which body was simply a part of a flat design. Byzantine artists were not interested in making figures true-to-life. They created a new style to show the spiritual nature of Christ and the nobility of the Emperor.

Periods

Byzantine art and architecture is divided into four periods by convention: the Early period, commencing with the Edict of Milan ( when Christian worship was legitimized) and the transfer to the Imperial seats to Constantinople, extends to AD 842, with the conclusion of Iconoclasm; the Middle, or high period, begins with the restorations of the icons in 843 and culminates in the Fall of Constantinople to the Crusaders in 1204; the Late period includes the electic osmosis between Western European and traditional Byzantine elements in art and architecture, and ends with the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The term post-Byzantine is then used for later years, whereas Neo-Byzantine is used for art and architecture from the 19th century onwards when the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire prompted a renewed appreciation of Byzantium by artists and historians alike.

-Wikipedia-

All Rights reserved. No part of this article

may be reproduced without special credits

in writing from the publishers in wikipedia.com, roman-empire.net, and thefreedictionary.com.