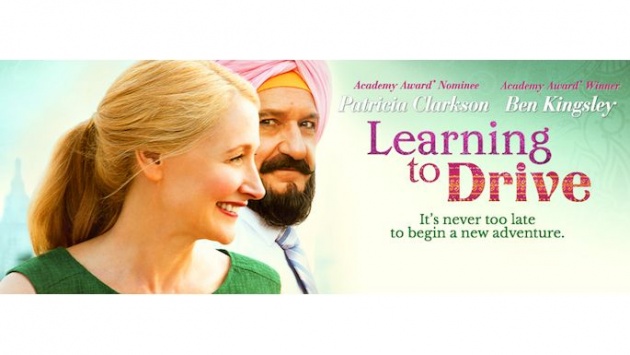

Patricia Clarkson is phee-nom-en-al as Wendy in the New York-set coming-to-terms-with-separation drama, Learning to Drive. Director Isabel Coixet’s film, from a screenplay by Sarah Kernochan, ostensibly begins with Wendy continuing an argument with her husband, Ted (Jake Weber) as he hails a cab. ‘You think that because you’re breaking up with me in a public place, I wouldn’t make a scene?’ We’ve seen the caricatured wronged woman in plenty of movies, but Clarkson’s Wendy is the real deal. She gets in that cab when her husband tries to escape to his lover’s house, but then he gets out and sends her home. The humiliation is crushing but the Sikh cab driver Darwan feels sorry for her and won’t let her pay for the ride. In her distress, she left something behind. Darwan returns it in the car he uses to give driving lessons and Wendy enrols as a means of paying him back. Only she can’t quite go through it. Darwan coaxes her into the car and the road to renewal opens up.

What is particularly brave about Coixet’s direction is that she never once allows Clarkson and Kingsley to look like they are playing characters who find each other’s wavelength. It’s about difference, making a bridge, but never quite sharing the moment.

Darwan isn’t as well written as Wendy but Kingsley brings something to the character – an insistence on correctness. Kingsley famously insists on his knighthood being acknowledged, a quality that serves him well here. Darwan has migrated to America to escape persecution in India and lives in Queens with a ragtag of immigration over-stayers, including his nephew (Avi Nash). In the only heavy-handed scene in the entire movie, the house is raided by police; the men are suspected terrorists. This doesn’t ring true, but it does clear the place out for Darwan’s new bride, Jasleen (Sarita Choudhury) – their marriage is arranged in the traditional way.

Wendy is a bit of a day dreamer and that makes her poor driver material. How can you pay attention to your surroundings when you imagine you are seeing your husband and her lover? Wendy has an adult daughter, Tasha (Grace Gummer), who gives her the impetus to drive when she settles on a farm, living on the soil. The only way Wendy can get to see her is by car.

Everything Darwan says in the car can be read as having metaphorical value, but Kernochan’s screenplay doesn’t go overboard on this. It is resolutely in the real world. Wendy works as a literary critic and I loved the cruel scene in which she goes on the radio to talk about how she loves words and certain authors, including the author who stole her husband.

The divorce battle is bitter, but as Wendy’s lawyer says, you are supposed to make outrageous demands to begin with – in this case on Wendy’s salary – in order that you can come down to an equitable arrangement. You can completely understand that Wendy wants to dress this up as some ’21 year itch’ (after the number of years they have been married). When Tasha says she can’t stay because she has been invited to dinner by her father, Wendy sees that Tasha is being used as a messenger and dismisses her.

The exploration of pain is acute, leavened only by Wendy’s one night stand who practices tantric sex, offering to make another appointment. (‘I could ejaculate on Thursday.’) It is contrasted with the prison that Jasleen finds herself in, too frightened to leave the basement flat to venture to the shops.

Very subtly the film points out that a sense of community develops more easily amongst the under-class than the privileged middle class; the former pay no heed to appearances and have common enemies. At one point, Darwan comes home to find his front room filled with women, Jasleen’s new friends. He willingly leaves, secretly pleased. It makes a change for gently chiding Jasleen for her ingredient-deficient cooking.

There are moments of real drama when Wendy stops suddenly and is tailgated; Darwan is attacked for his appearance. Wendy rushes to his defence: ‘that’s blatant racial profiling.’ There is a thrilling sequence when Wendy drives over a bridge for the first time, having to overcome her vertigo.

The finale shows how far Darwan and Wendy really are from one another; the awkwardness of the final exchange between two people who remain in different worlds. Coixet has worked with Kingsley before on the drama, Elegy (2008) in which he starred opposite Penelope Cruz. You sense that director and actor trust each other for the former to deliver a compressed, minimalist performance. This is a comparatively rare example of a female director building a professional collaborative relationship with a male star; Penny Marshall did something similar with Tom Hanks, working with him on both Big and A League of Their Own.

The credits of Learning to Drive deliver a nice surprise, that the film was edited by Thelma Schoonmaker, who normally only works with Martin Scorsese. Her editing is crisp and no fuss. The only thing Learning to Drive has in common with a Scorsese film is the frequent panning from one character to another.

Since Learning to Drive, Coixet (born in Barcelona, Spain on April 9th 1960) has completed another film, Nobody Wants the Night, starring Juliette Binoche. Her later film opened the 2015 Berlin Film Festival to mixed reviews and has been re-edited prior to release. Fans of Coixet’s early work will notice a copy of ‘My Life Without Me’ amongst Wendy’s books, a reference to her 2003 film starring Sarah Polley.

Reviewed at Crouch End PictureHouse (Screen Four), North London, Monday 20 June 2016, 18:25 screening