|

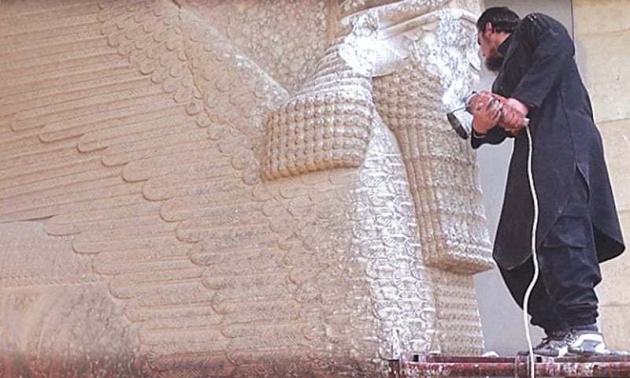

A militant uses a power tool to destroy a winged bull at the museum in Mosul

|

Recently, the extensive list of horrors perpetrated by Daesh across Syria and Northern Iraq grew upsettingly longer. In Mosul, the largest city under Daesh control, groups of men reportedly destroyed the city’s public library with improvised explosives, torching some 10,000 books in the process, and incinerating hundreds of rare manuscripts. Shortly after, videos surfaced of men hacking away at priceless statues from the Assyrian and Akkadian eras in Mosul’s central museum, and toppling them to the ground.

It has since been suggested that many of the smashed statues were, in fact, replicas. Even if true, the malevolence of the act itself is no less appalling. And given all the other loss of priceless artefacts, not to mention the razing of Mosul’s library, the possibility that mere copies of ancient art comprised some of the total destruction offers little more than cold comfort.

Almost immediately after the video began circulating on the internet, debates about sharing these unsettling images erupted on social media. Some questioned the appropriateness of lamenting the destruction of inanimate objects while the staggering human costs of the Daesh’s occupation grow by the day. Others argued that that the dissemination of Daesh propaganda serves to empower the group further, and should therefore be avoided.

Far from shying away from these shocking acts of cultural desecration, it is imperative that we strive to understand what they represent and think through the ways in which they serve the Daesh’s political agenda.

To begin with, the wanton destruction of cultural heritage is hardly unprecedented. The annals of antiquity are littered with cases in which marauding hordes smash idols, burn libraries to the ground and otherwise attempt to extinguish any record of artistic achievement. To be sure, the modern vandal descends from the eponymous Scandinavian tribe that famously sacked Rome and set the stage for Europe’s slow slide into the Dark Ages.

“The first step to liquidating a people is to erase its memory. … Before long the nation will begin to

forget what it is and what it was. The world around it will forget even faster.” — Gustav Husak

The recent past has hardly been more enlightened. In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that we live in an age in which the world’s great monuments are routinely under attack. A quick survey of the recent past might include the dismantling of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, India; the obliteration of historically significant bridges and monuments in Mostar, Bosnia; the Taliban’s demolition of the 2,000-year-old Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan; the looting of libraries and museums in Iraq following the American invasion in 2003; the destruction of ancient manuscripts and monuments in Timbuktu, Mali; the devastation that civil war wrought on Syria’s grand heritage sites well before the Daesh came on the scene, and so on.

Statues were destroyed on the pretext that they promote idolatry / Screen grabs from Daesh video

Daesh’s behaviour as something uniquely sinister and new. Many of these arguments conveniently boil it all down to the nature of Islamic extremism, and the particularly virulent strain infecting followers of Daesh. Yet when the sacking of Mosul’s museum and library is examined more deeply, it becomes evident that Islam plays only vague role in the destruction, offering nothing more than a sort of branded packaging of its own imperial language. The Daesh’s actions are less directly about religious ideology than they are about increasing political power and consolidating it. Iraq has borne a disproportionate spate of bad luck when it comes to the erasure of its heritage. During the American invasion of 2003, it was widely acknowledged that troops watched nonchalantly while Baghdad’s national museum was looted. Donald Rumsfeld shook it off with “stuff happens”. But as weeks went by without any of the promised protection being provided to the now ruined museum, this nonchalance appeared more resolute and deliberate leading critics to believe that the American government was indeed invested in a kind of cultural cleansing.

Sledgehammers were used to smash exhibits / Screen grabs from Daesh video

Now, over a decade later, the Daesh appears to be pursuing somewhat similar goals. Firstly, they are carrying out an ongoing imperial project across Syria and Iraq, and these are unabashed attempts to carve out a fresh narrative of power to demarcate territory and redefine it without remorse. Far from being something new, the violent erasure of historical memory has been a recurring feature of state-making efforts by occupying powers.

Without properly situating the Daesh’s latest actions in Mosul, other, more destructive narratives will be allowed to take hold. Given the Daesh’s ultraviolent campaign across the Middle East, labelling them barbarians and calling for their defeat might seem entirely reasonable to some. At the same time, these sorts of reactions — born of anger, outrage and fear — are easily reduced to essentialist ideologies pitting “us” against “them” in some grand clash of civilisations that has no basis in reality.Failure to confront these realities will allow for greater levels of violence, death and destruction perpetrated by all sides.

Bhakti Shringarpure is the Editor-in-Chief of Warscapes magazine, and Assistant Professor of English at the University of Connecticut. Twitter at @bhakti_shringa.

Michael Busch is Senior Editor at Warscapes magazine, and a doctoral candidate in International Relations at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. Twitter at @michaelkbusch.